by Carrie Devall

One of the biggest pleasures for me in 2014 has been a two-year-old Border Collie/Siberian Husky mix named Betty. The MN Border Collie Rescue saved her from an animal hoarding situation, and she was terrified of people, even after being with her foster hosts for almost a year. However, a ton of treats and a pack and comfort dog of her own have let her sneaky, goofy, bit-of-a-princess personality blossom. I spent a lot of time this year about the gross mistreatment of dogs and about their resilience on animal rescue sites. I'm realizing in retrospect that a lot of the books I read this year also focused on animal and human behavior, and in particular animal violence and human cruelty, or “inhumane treatment,” as they say.

I saw a bunch of international films at the the MSP International Film Festival, though not half as many as I wish I could have seen, looking through the catalog again. The best these were about harsh landscapes and human cruelty towards other humans and animals, except for one. Purgatorio: A Journey Into the Heart of the Border was a very personal film by Rodrigo Reyes, who came to speak at the showing. I though he ably showed some of the stark contradictions in life at the U.S.-Mexico border, where I once worked for legal aid, though some audience members did not like the part that showed the mistreatment of stray dogs to raise questions about treatment of humans.

Harmony Lessons was an engrossing movie from a young Kazakh director that used graphic images and a pattern of violence among high school boys in a metafictional discussion of torture, power, and control, I assume alluding to both the Kazakh and Russian governments. The documentary Dangerous Acts Starring the Unstable Elements of Belarus followed a troupe of actors as they fought against repression while the dictator staged his re-election. This was another very well-made film where the graphic violence was not at all gratuitous.

On the flip side, We Are The Best was a fun and easygoing film about Swedish girls in the early 1980s Death to Prom was a locally-made film with a multiracial cast that I remember being very funny and charming though the actual plot has escaped me beyond the guy and girl who are artists and best friends competing for the hot new Russian boy at their high school. Belle falls more into the serious side as it was based loosely on a true story and explored the legal status of freed slaves in the eighteenth century through the vehicle of a costume drama.

who fought everyday sexism with punk rock, by Lucas Moodysson. It was refreshing to see a film that focused on girls without being difficult to watch or stupid, and the music and 80s hair is great. (Check out the trailer.)

I just finished Karen Joy Fowler's book from 2013, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, which I found to be very gripping and insightful, my two go-to words to describe books I read from cover to cover in less than a day or two. It's hard to have too much to say about this book without giving away spoilers, because so much of the style of the book has to do with surprises, revisions, and questions about memory. I also say “insightful” with a caveat: that sharp insight into human character and behavior and our treatment of animals, and into family dynamics, can be deeply disturbing.

Another novel that dealt with disturbing questions in a deceptively 'easy' style and is difficult to put into an elevator pitch was Tehran in Twilight by Salar Abdoh, a noirish novel of political intrigue set in New York and Tehran. Often reading like cynical poetry, this novel has a meditative pace but covers an immense amount of internal and external territory in amazingly few words.

I also just read the book I'd been waiting all year for, which got rave reviews outside the US and then was delayed in being released here. For the record, wikipedia would tell you that Johanna Sinisalo is a Finnish writer who has won Nebula and Tiptree awards, respectively, for English translations of the short story "Baby Doll" and novel Troll: A Love Story (U.S. translation)/Not Before Sunset (U.K. translation), as well as the Finlandia prize for Troll in the original.

While waiting for her new novel, I reread her available fiction and the Daedalus anthology of Finnish Fantasy translated into English that she edited. That contains many intriguing stories, including a rollicking tale about a wily dog demon. I'm always surprised how few fans of feminist SFF seem to have read her work, because I can't stop rereading regularly for the pleasures of finding the deeper layers and more subtle nuances. I am hoping folks will work to make Worldcon go to Helskini in 2017(!) so the work of Sinisalo and other great Finnish writers will get more play. (See Cheeky Monkey Press, also.)

While Troll focused on Finnish characters and folklore, Birdbrain decentered Finland. The protagonists, a newly-coupled young Finnish man and woman, go on a trek through relatively “untouched” wilderness in Australia and Tasmania. Birdbrain explores, among many related themes and conflicts, the relationships of humans to animals and of Westerners and Europeans to the globe as a living entity and its many other peoples, also in amazingly few words.

Ostensibly moving back to Finland as the setting, Enkelten Verta, translated as The Blood of Angels, sets its gunsights on the dirty secrets and grimy underbelly of BigAg as well as the contradictions inherent in animal rights activism against it. Sinisalo uses blog entries as the lifeline that links the greater world, the “real world,” to the protagonist, a bee farmer in rural Finland who steps into and out of present reality/spacetime that is linked to the massive die-offs and disappearances of bees. The novel's action takes place in that kind of ethereal near-future-yet-already-here timeline that William Gibson has set up in his recent novels, taking that one small step from events happening now IRL (bee colony collapse) to the possible logical outcomes that may already be underway as we read and share the book.

The end result is a terse but lyrical hybrid of science fiction and fantasy similar to the other two nooks, here weaving speculation in with the characters' highly politicized opinions about the underlying causes of the bee colony collapse syndrome. Angels hides its feminist hand a lot more than the earlier two novels. However, for starters, the fact that the women of this world are so obviously missing from the web of relationships that connect the characters is a statement in itself.

The same translator, Lola Rodgers, translated another book I enjoyed this year, a science fictional noir novel with similar themes and setting in a near-future Finland in the midst of global environmental collapse. After working on learning Finnish through Teach Yourself books, I can say pretty assuredly that the challenges of translating the subtleties of Sinisalo's wordplay and so-dry-you-might-miss-them witticisms between languages as different as Finnish and English have got to be daunting. It also seems like misplaced energy to try and render judgment about a particular translation of Sinisalo when she reads so well across translations. I could say that Rodgers' translations seemed particularly smooth and skillful, but that would only really be saying that I found both books very readable.

In Antti Tuomainen's The Healer, a poet searches for his wife, a journalist who has gone missing while researching a story about a serial killer. The pacing of the unraveling of the mysteries of the wife's disappearance and the role of the serial killer was pretty brisk. Hamid, a recent North African immigrant who drives a cab, assists him for a complex mix of reasons. I had trouble deciding whether this was simply another Magical Negro role or at least a partial escape from that trap, but it seems to represent a small step forward for the prominent books in the “Scandinoir” framework. The generous handful of Scandinavian crime/noir novels I read over the last year discussed race and immigration mostly by having gangster and skinhead characters commit racial assaults as a showy backdrop to the anti-hero's battle against criminal masterminds. It was interesting to see a Finnish book, out of the few marketed to an English speaking audience, that tried to grapple with race in present-day Finland. Sinisalo's books have some characters rant about the history of global slavery and exploitation but do not really attempt that task.

I've really enjoyed the Skiffy and Fanty podcast series on World SFF, too, for the wide variety of people and con panels and in-depth discussions.

Away from SSF, Pissing In a River was the long-awaited follow-up for Lorrie Sprecher, who wrote Sister Safety Pin, another novel about dykes who love punk rock and get involved in AIDS activism in the 1980s. Both novels center on women who are navigating relationships with each other while dealing the impact of male violence against them in the recent past. I thought Pissing In a River had a more complex and emotionally moving storyline, but I like that both books deal with sexual assault (and PIR with OCD) as something the characters are dealing with in their busy and complicated lives instead of a gratuitous plot device.

Eating Fire: My Life as a Lesbian Avenger, by Kelly Cogswell, pretty much explains its premise in

the title. This book got hella things right in terms of describing the in-fighting and ridiculousness of direct action affinity group activism in the most loving and nostalgic possible terms. It also also names bad choices, racism, and internalized homophobia for what they were in the moment and the movements of the time. This book is not just a list of the cool things a bunch of activists did or a recounting of how they did it, but also a parsing of what worked and what did not and why choices that proved detrimental to the overall project and individual actions were made. Cogswell was in an interesting position in terms of viewing and intervening in the racial dynamics of the NYC Avengers, and she also explores the challenges she and her Cuban partner faced in their relationship and with the Avengers.

I found Sarah Waters' new novel, The Paying Guests, to be one of her strongest yet, along with Affinity and The Night Watch. I am generally not a big fan of historical novels with rich period detail, but this is reliably the aspect of her novels which draws me into her stories. This one truly is ripped straight out of a tabloid headline, about a murder trial. It's not simply a bodice ripper and neither a murder mystery, but a little of both.

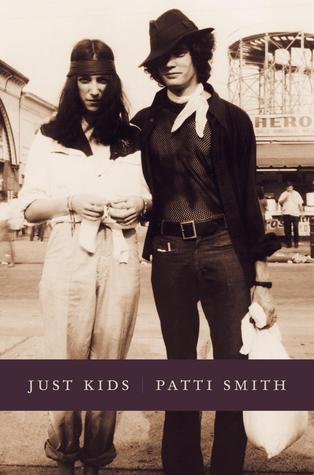

I read a lot of biographies of queer activists and artists focused on a certain era, the 1970s to early 1990s. Among the ones I liked the best were Just Kids, Patti Smith's book about her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe, because it touched on both the punk music and fine art scenes of the time and really got into both the spiritual aspects of the creative process, the business aspects of these arts, and the gritty realities of life as an artist. Cynthia Carr's biography of David Wojnarowicz, Fire in the Belly, was an eye opener for me because I had read his books but not seen his art, and the biography has great color plates of many of his paintings and photos. In a nutshell, both men died from complications associated with AIDS and were fierce fighters against right wing attacks on their art and arts funding for similarly challenging work, the not-coincidentally recurrent theme in queer artist/writer biographies from this era. I also finally saw The Dallas Buyer's Club, which had a lot of flaws but ultimately did a decent job of viscerally depicting the root of the raw fury that fueled AIDS activism before the cocktail.

I read a lot of biographies of queer activists and artists focused on a certain era, the 1970s to early 1990s. Among the ones I liked the best were Just Kids, Patti Smith's book about her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe, because it touched on both the punk music and fine art scenes of the time and really got into both the spiritual aspects of the creative process, the business aspects of these arts, and the gritty realities of life as an artist. Cynthia Carr's biography of David Wojnarowicz, Fire in the Belly, was an eye opener for me because I had read his books but not seen his art, and the biography has great color plates of many of his paintings and photos. In a nutshell, both men died from complications associated with AIDS and were fierce fighters against right wing attacks on their art and arts funding for similarly challenging work, the not-coincidentally recurrent theme in queer artist/writer biographies from this era. I also finally saw The Dallas Buyer's Club, which had a lot of flaws but ultimately did a decent job of viscerally depicting the root of the raw fury that fueled AIDS activism before the cocktail.

Martin Duberman's biography of Essex Hemphill and Michael Callen, Hold Tight Gently, mines similar territory. Essex Hemphill was an African American poet from Washington, D.C., who founded, co-founded, and helped nurture a wide array of organizations and literary magazines, readings, etc. His life became closely intertwined with that of Joseph Beam, who edited the groundbreaking anthology In The Life, and they co-edited Brother to Brother. Michael Callen was a white singer and AIDS activist who bucked the gay and both the AIDS activism and industry establishments with a no-b.s. approach towards the scientific data available about longterm survival with HIV. All three men were heroes to me as a baby dyke. Duberman's biography delves deeply into the history of seemingly everyone and everything both subjects were involved in as well as their own personal histories, with all their human contradictions. Like Cogswell, he covers in detail many of the controversies and conflicts that came up in the artistic and activist organizations and movements they were involved in, making this a history of an era as much as a split biography.

Christopher Bram's biography of a generation (or three) of gay writers, Eminent Outlaws, was also a good read. While it is hard not to think of it as the story of the white gay canon plus James Baldwin, I found that I knew less about that canon than I thought, despite having read many of the novels and stories they wrote and a lot about their personal histories in the course of following gay lit over many decades. Bram provides concise yet detailed intertwined biographies of writers but also focuses on the larger social forces they faced, particularly publishing industry homophobia.

On a completely different note, I was surprised to enjoy Stephen King's sequel to The Shining as much as I did. The antagonists in Doctor Sleep were truly creepy, though not at all like the Overlook Hotel. This is one I would not recommend to people who are squeamish or reactive to repeated musings about child abuse or cravings for alcohol, but it makes a right proper horror story out of these longtime King themes without being a retread.

Carrie Devall lives in Minneapolis and has been told so many times that she spends too much time working and not enough time writing that it just might be true.

No comments:

Post a Comment