Year in Reading — 2019

by Christopher Brown

The book that

consumed me the most this past year was an old one, and one I had read before,

albeit in a different translation. Njal’s Saga is a 13th century epic about a

lawyer in 9th century Iceland who specializes in complex settlements

of family feuds. That the settlements never stick for long is kind of the main

point of the story—someone always breaks the peace, and the cycle of violence

renews over generations. I re-read Njal

in search of the deep roots of the lawyer story, and it holds up well in that

regard, especially since the system of proto-torts that bound that society

together was very close to our own Anglo-Saxon roots. More surprising was to

see how much the saga works in some of the same ways as a science fiction

colonization story—a tale of people settling a hostile landscape in which the

only other human inhabitants found upon their arrival were a few Irish hermits

sequestered in coastal caves, and a story that shows how the basic systems

human societies create to resolve disputes by means other than violence are the

essence of government.

In my year-end round-up here for 2016, I talked about another of the Icelandic

sagas, Laxdaela

Saga, and its

storyline about Unn the Deep-Minded, a female Viking and sage who found herself

leading her people and managed to briefly establish a kind of intentional

community founded on equitable distributions of property, the abolition of

forced servitude, and more just governance. The negative space of those stories

opens portals into possibility, in the unrecorded histories of those who tried

a different path, the kind of utopian path that small groups can manage where

large permanent settlements cannot.

The world of Njal,

crippled by the unceasing blood feuds of men who divided up the land and

reflexively drew their swords to settle the merest slights, was also the world

of Unn, who founded a community based on an ethos of sharing. That the world of

Unn could only exist as an ephemeral island in a sea of Viking raiders tells a

lot about the challenges of constructing utopia, even in terra nullius.

The search for

examples of other such islands drove the wide-ranging research reading I

undertook this year while working on my new book, Failed

State, about a lawyer representing

people who have been hauled in front of a post-revolutionary justice tribunal—a

utopian legal thriller, to bookend my dystopian legal thriller, Rule

of Capture, which came

out this past summer. Utopia is nowhere, but it is rewarding to search for.

I learned that

Gudrun Ensslin called consumer society “the raspberry Reich,” and that her

comrade in arms Andreas Baader insisted on wearing his favorite hip-hugging

velvet trousers instead of army fatigues even while training for combat at a

PLO camp in the Jordanian desert. The

Baader-Meinhof Group

by Stefan Aust, a journalist who worked with Ulrike Meinhof in the early days and

was exceptionally close to the material, is a remarkable examination of how youthful

political activism evolved into armed struggle in West Germany. It was one of

many books about revolution and justice I read or re-read, including a number

from or about Germany: Peter Weiss’s masterful The

Investigation, which

repurposed transcripts from the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials as the material for

a remarkable stage play; Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann

in Jerusalem; Abby

Mann’s Judgment

at Nuremberg; and

Leora Bilsky’s The

Holocaust, Corporations and the Law.

I read one new

book in Spanish, El

Comensal by Gabriela

Ybarra (published in English as The

Dinner Guest), an

intense and compelling short novel about the author’s investigation of her own

grandfather’s kidnapping and murder by Basque terrorists in the 1970s. I read

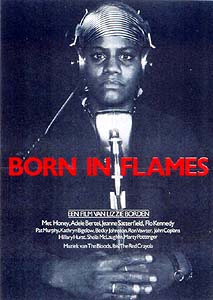

Chinua Achebe’s collection Girls

at War, the engaging

title story of which is a curious example of the way certain writers

romanticize the figure of the female revolutionary (this writer included). I

re-read Graham Greene’s The Comedians, his novel of the Haitian revolution, and

found that the languorous charisma of the author’s late colonial decadence does

not age well. I read Sophie Wahnich’s In

Defense of the Terror,

a fresh critical reconsideration of the French Revolution and its hagiography.

And I read Paul Krassner’s Patty

Hearst & The Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials, the satirist’s insightful diary of two

very different but both uniquely American prosecutions of political violence in

the 1970s.

Gina Apostol’s Insurrecto was one of the best new books of the year

for me, an innovative story about two women collaborating on a project: a

Philippine translator recently returned to her home country from New York, who

gets hired to help a documentary filmmaker research her own father’s filming of

a Vietnam War movie there decades earlier (think Apocalypse Now or Platoon).

As they seek out the locations from the film, they confront more authentic

atrocities, and uncover layers of erasure and colonization in the process.

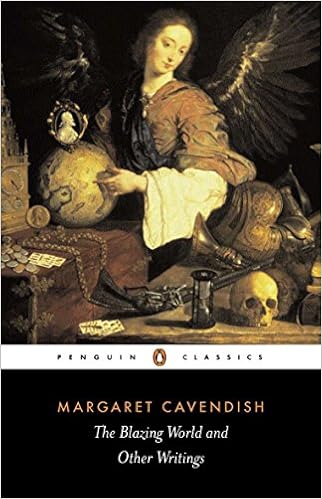

I also sampled a number

of utopian novels, from More’s eponymous classic to SF masters like Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed (re-“read” as an engaging audiobook) and The

Word for World is Forest,

Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge, and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. I even re-read chunks of James Hilton’s

Shangri-La fantasy Lost

Horizon, which I had

read as a teen. More interestingly, many of the books I picked up this year for

other reasons turn out in retrospective consideration to have been works I

would categorize as utopian. Longer by Michael Blumlein is a beautiful science

fiction novella about age and longevity, from one of our most unique

contemporary sf writers, a physician who at the time he was working on the book

was also facing the cancer that sadly took his life this fall. (Blumlein’s Thoreau’s

Microscope, like the

Krassner part of PM Press’s outstanding Outspoken Authors series edited by

Terry Bisson, is another amazing one I had the fortune to read this year,

especially memorable for the title essay in which the author considers the

wonder of his own cancer cells as viewed through the microscope.) Jessica

Reisman’s The

Arcana of Maps compiles

a beautifully written array of stories about communities of people trying to

build better realities free of conflict. Tears

of the Trufflepig, the

debut novel of Fernando Flores, is a literary dystopia of the Texas-Mexico

borderlands that somehow harbors a utopian mirror in the memory of the reader.

And Erik Davis’s High

Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica and Visionary Experience in the Seventies interestingly synthesizes the utopian

proclivities found in the works of Robert Anton Wilson, Terrence McKenna and

Philip K. Dick and their tripped-out searches for paths to higher awareness.

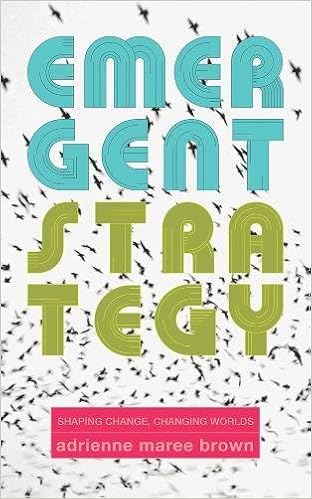

Ecological

concerns appear in most of those utopian books, and much of the nonfiction

ecology writing I read this year also straddled the utopia/dystopia axis, for

obvious reasons. Silvia Federici’s Re-Enchanting

the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons collects an engaging body of radical

essays on capitalism, feminism, and our relationship with the land. Ashley

Dawson’s Extreme

Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change argues the utopian potential to reorganize

more equitable and just community structures in response to the threat of

climate crisis. The

Uninhabitable Earth by

David Wallace-Wells is more grim, a travelogue of what he presents as the

inevitable state of the near-future world absent dramatic action to change our

collective behaviors. Seeing Like a State by James Scott weighs against the

possibility of utopia, and maybe even of any authentic capacity for pur

collective self-improvement, with an incisive critique of the hubris inherent

in human efforts to engineer better political economies atop natural systems. Along

with Scott’s more recent Against

the Grain, a deep

history of the Anthropocene which I mentioned here last year, a compelling case is made that the only

real solutions to our current ecological problems lie in a radical reworking of

some of the fundamental socio-economic structures that were created by (and

helped create) the agricultural revolution—a revelation of impossibility that

suggests the Cassandras like Wallace-Wells may be more accurate in their dismal

prognostications than I am inclined to believe.

As tonic for all

this, at the end of the year I discovered a book called Frauen

Auf Bäumen (Women in Trees) by Jochen Reiss, a book

of found amateur photos of just what the title promises. I am not sure why, but

when I picked the book up for my wife and daughter, I thought it was the most

utopian thing I could find, encoding some oblique answers as to where a

healthier future lies. Maybe even by climbing back into the trees, or at least

planting enough of them to start our way back.

Christopher Brown’s novel Tropic of Kansas was a finalist for the 2018 Campbell Award for best science fiction novel of the year. His latest novel, Rule of Capture, was published by Harper Voyager in 2019. He lives in Austin, where he also practices law.