by Sarah Tolmie

First off, if you read poetry, you should read Kim Hyesoon’s The Autobiography of Death (translated by Don Mee Choi, New Directions, 2018). Even if you don’t read poetry you should read it. Though you may hate it; it isn’t poetry for the inexperienced. It’s one of the best books I have read in a long time. The raw nerve it takes to write an autobiography of the force that destroys the subject, that de facto has no story and is inaccessible to consciousness — well, it is awesome in the fullest sense of the word. Here is a woman attempting to do the impossible. I can’t give her enough points for style.

I was on sabbatical for part of this year, continuing my odyssey through the world of audiobooks. I am still totally on a roll with this format, to my surprise. As I think I may have mentioned last year, I got into this following eye surgery — now I can’t give it up. We always read aloud to our kids, teenagers now and busy with their own stuff, so maybe it has to do with a certain nostalgia for the voice. Anyway, it has become the medium in which I undertook a project of filling in the gaps in my reading of 19th-century novels. I don’t exactly write naturalistic fiction myself, but I have always admired it, and plenty of the major British and Russian novelists stray into expressionism and use fantastic effects unashamedly. For one thing, having heard a bit more Dickens — Richard Armitage’s excellent David Copperfield for Audible and Mil Nicholson’s Our Mutual Friend for Librivox — the extent of his influence on Mervyn Peake (whose Gormenghast trilogy is gorgeously performed by Saul Reichlin, by the way) as well as on Neil Gaiman has become ever more clear to me. The grotesque Christmas story The Chimes, for example, could almost have been written by either of them. (The multi-cast production of Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, incidentally, deserves mention here. As a rule I do not like dramatizations with a full cast and music and all the rest of it, but this is a good one.) I listened to all of the works of George Eliot, who was a towering genius. Juliet Stevenson does inimitable readings of Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda. Just amazing.

I finally became acquainted with the major Victorian novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, who wrote, among other things, North and South. Her grimdark take on the industrial north is quite the eye-opener, let me tell you, in books like Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life and several others. I completely missed her in school and it was a real gap in my feminist education. I listened to some Trollope, which was more entertaining than I thought it would be, and to Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, that fountainhead of the mystery genre (really interesting, especially considering that one of its central characters is a “halfwit” who is viewed in a quite multifaceted way). I tried to listen to The Return of the Native and realized that Thomas Hardy is an ass. Not even the luscious reading of Alan Rickman was able to rescue it.

Then there was a lineup of celebrated Russians. There are numerous recordings of most of these. I went with Constantine Gregory for many of them. The Brothers Karamazov is a book that nearly roasted to death on my back burner: it’s a flawed gem in many respects but I am glad I know it in its entirety now, and I can certainly appreciate its influence. Gogol was a revelation, especially Dead Souls. Lermontov’s A Hero For Our Time is bleakly wonderful — it provided the epigraphs for both my latest poetry collection and short fiction collection — and Tergenev’s Fathers and Sons is a wonderfully humane book, all things considered. The crowning glory of them all, though, both as a book in itself and as a recorded performance, was Julian Rhind-Tutt reading Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Rhind-Tutt is that rather leonine fellow you may remember as the evil elder brother in Harlots — he has one of those signature velvety baritones and seems to have been made to read this book. The work itself is terrifyingly good. Bulgakov’s life was such a disaster that it is heartbreaking to consider that he never knew what a success it became. It is pretty damn clear where Sympathy For The Devil came from. If you listen to one audiobook in your life, make it this one. I have developed a weird passion for turning it into a libretto (the book, that is); it is perfect opera material. Wow.

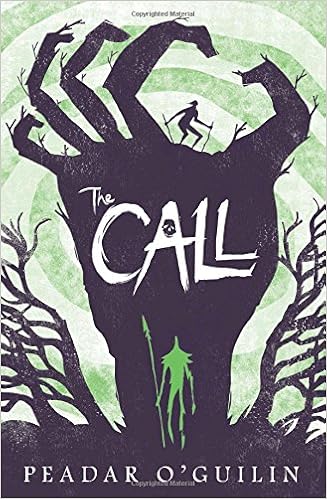

I should also put in a good word for Peadar O’Guilin’s YA books The Call and The Invasion, which I read back-to-back. Very pacey and gripping, though not for the faint of heart when it comes to body horror. A really good use of Irish mythology.

And yes, I am watching Jack Thorne’s adaptation of His Dark Materials. I have been waiting and waiting for it, as Pullman’s series is one of the major achievements in fiction of the last 20 years — and my gods, was the movie ever bad. It deserved better and it seems to be getting it. Cast is spot-on everywhere (except for Mrs Coulter, alas, who I don’t like at all — though there is at least a plausible resemblance between mother and daughter) and, amazingly enough, they are letting the story unfold at a reasonable pace instead of making it into a CGI action nightmare. Let’s hope they can keep it together through the climax.

Best wishes to all for 2020, and happy reading!

Aqueduct Press has published four of Sarah Tolmie's marvelous books: The Stone Boatmen in 2014, NoFood in 2014, Two Travelers in 2016 and this year, The Little Animals. Sarah is also a poet; and has published two collections, Trio in 2015, and The Art of Dying in 2018. She is an Associate Professor in the English Department at the University of Waterloo. Her author site is sarahtolmie.ca.

No comments:

Post a Comment