Always Reading in 2023

By Nancy Jane Moore

We are

slowly being crowded out of our apartment by books. We buy them. We pick them

up on the street and in little free libraries. We check them out of the public

library. We keep trying to get rid of the ones we don’t want, but that requires

us to both decide we don’t want something and then for one of us to actually

take it out of the place.

Things would

be worse if it wasn’t for ebooks. I’ve got three reading apps and two library

apps for those. Plus magazines also take up space, especially New Scientist,

which comes weekly. We keep trying to throw magazines out (or put them on the

street for others), but it’s hard to be sure we’ve finished with them.

And of

course, I read magazines and newspapers and newsletters online as well, not to

mention various and sundry articles and blogs I stumble across. The truth is

that my partner and I are always reading. It makes figuring out which books and

other things to write about a challenge, because I can’t write about them all.

So instead of trying to include everything I read this year, I want to focus on two books that affected me profoundly and deeply. Two very different books.

The first is Menewood by Nicola Griffith. This is the sequel to Hild, which I also loved, but Menewood is so much more than a sequel. First of all, looking at it as a writer, it is simply a brilliant piece of written work. It’s 681 pages long (not counting notes and maps) and every page, every sentence, every word matters. I, who often skim through long and exciting books because I want to know what happens next, read every damn word. It took me five days and cost me sleep because I had some important things I also had to do. I could not put it down for long.

My passion

for this book goes beyond the sheer beauty of the writing. While it shows

Griffith’s depth of knowledge of the history of England in the seventh century

(long before it was even one small country, much less an empire), it is much

more than a good historical novel. Yes, of course, a lot of is made up, for so

much of the history of that time is unknown. But Griffith has wedded her

knowledge of the things that did happen with her speculative fiction writer’s

ability to come up with what could have happened within the context of that

reality. She made it up, but it fits.

And even more importantly to me, she has written a book about what true leaders do, and should do. The “kings” of English history in this time are warlords contending with each other for land and power and wealth. Each kingdom is tiny, by today’s standards, and each king has ambition for more. But, like all too many leaders even of large countries, not to mention corporate barons of today, they want that power and wealth for its own sake, not for what they can do with it for their people.

Hild is a

woman with a lot of power, but she is different from those kings. Reading this

book makes one see what a world could be like with true leadership.

This is a masterpiece

of literature and Griffith’s best book yet. I have read all her novels and a

good chunk of her short fiction and have been a fan of her work for a very long

time, but this book crosses a threshold.

If you

haven’t read Hild, read it first. Menewood transcends that very

good book, but the underpinnings are important.

The second book is completely different: How Infrastructure Works, by engineering professor Deb Chachra. This deeply important book delves into the many systems that underlie our modern world – electricity, international shipping, roads, communications, plumbing – and makes it clear how essential they are.

Chachra

makes several important points in this book. First of all, infrastructure

systems are, by their very nature, collective. They are used by many people at

once and work best when they are operated with that in mind.

Secondly,

most crucial infrastructure is relatively new, having been developed within the

last couple of hundred years. While roads have been around for millennia, the

sheer number of highways that were built over the 20th century to accommodate

the automobile boggles my mind when I think about it.

Third,

infrastructure is what makes modern life modern. Without it, people must devote

all their time to the basic tasks of life. If your home lacks running water,

you must fetch it. If it lacks refrigeration, you can’t store food. Without a

sewer system, you face challenges in dealing with human waste. Off the grid

life may sound “free,” but modern systems are what gives us the time and space

to do more with our lives than the basics.

Fourthly,

and perhaps most importantly, infrastructure is something we humans invented.

Unlike natural systems, it is not unchangeable. Not only that, but we can learn

from our errors if we look at the system carefully. For example, people assumed

that widening highways would solve traffic problems, but instead, that tends to

increase traffic because more people use the road. And drainage systems that

dump waste into rivers or even oceans have created new problems.

Much of our

current infrastructure was created around fossil fuels, but here is the part of

the book that gives me the most hope: Chachra says we can build a future that

provides sufficient infrastructure to give all of us the systems we need to

make life reasonable and comfortable from renewable energy sources. This will

require redoing current infrastructure, which also will give us the opportunity

to make different decisions about what we need. (Maybe we don’t need all those

cars and roads.)

And once we

do that, the energy to run our world will cost almost nothing, especially by

comparison to fossil fuels. There are some technological challenges still, but

the bigger ones are societal and political.

I’ve tried

to summarize why I find this book so constructive, but I still feel like I’m

not doing it justice. The writing is delightful, clear to a lay person like

myself without being condescending. Chachra manages the trick of being honest

about the challenges we face while still being optimistic about what we can do.

The information is vital to everyone from the writer who wants to creature a

non-dystopic future to the activist dealing with climate change to any person

frustrated with badly run utilities and overcrowded highways.

I want

everyone to read this book!

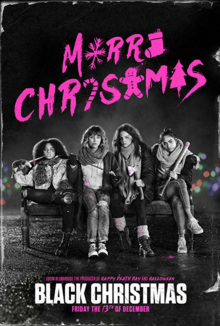

I’m so far behind on seeing movies that it’s almost silly for me to comment on them. But I do want to mention one movie that I think most people missed: the 2019 slasher film Black Christmas. (This is a remake of two earlier movies with the same name, so the date of release is important.)

I actually

saw this movie at the end of 2019, but I watched it again this year because I

wanted to discuss it in an academic paper for WisCon. It’s one of the most feminist

movies I’ve ever seen, which is not something you expect from a slasher film.

This

particular movie roots the violence necessary to the genre in misogyny and most

of the murder victims are women. In one healthy improvement to the genre, the

camera does not dwell on dead female bodies.

But more

than that, the women students fight back even though they are not superheroes

or trained fighters, and they fight back collectively. This movie does not show

women as powerless and it shows the importance of doing things together.

I found it

much more inspiring than the various movies about women superheroes. Give me an

ordinary hero any day.

I will

confess that I found the movie a little harder to watch the second time because

I knew that characters I was invested in were going to die. I don’t usually

watch slasher movies or recommend them. But this one did inspire me and I’d

like to see it get more of a following.

One other

thing I did this year was become obsessed about so-called artificial intelligence

as represented by the large language model (LLM) chatbots that were released

into the wild with great hype and even greater flaws. There are many ways of

looking at those programs; I know some writers very angry because their work

was used in developing the LLMs and others who have lost the kind of steady

freelance jobs that paid their bills because some fool thought they could be

replaced with a program.

But while

those things are a concern, I find them just one part of a much larger set of

issues. Not, I hasten to add, the laughable idea that these LLMs will become

true artificial general intelligence and either bring about some kind of

salvation or destroy the word; contrary to the tech bro vision, neither the Terminator

nor the Matrix movies are documentaries.

Unfortunately,

much of the popular media coverage of these LLMs has been uncritical reports

based on the hype laid out by Open AI and the other companies, leaving out the

very real criticisms leveled by those who are generally called ethicists –

people who understand what this tech is doing and who see a number of problems

that aren’t even being considered, starting with the fact that most LLMs make

some serious errors that can be dangerous if they are used for such things as

facial recognition systems, just to pick one.

There is a lot of good material out there. I want to point to two good starting places for examining the deeper issues. One is the academic paper “On the Danger of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” by Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell, and Angelina McMillan-Major. It was this paper that got Gebru and Mitchell fired from Google.

The other is

an article by Ted Chiang in the New Yorker: “ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPG of

the Web,” in which he describes the chatbots as “lossy text-compression

algorithms.”

Both these

pieces undercut the popular narrative and make clear that we’re a long way from

real AI. They also make it clear that we need to stop falling for tech bro hype

and start questioning and regulating the products that come out of that world.

The copyright lawsuits currently pending may help, but the problems created by

LLMs are much broader than the immediate issues of writers and publishers.

As I was

about to send this piece off to Aqueduct, I read the latest newsletter from

Dave Karpf, a professor who studies the internet and politics. He suggests two things that may happen with LLMs that will change the pop

narrative and perhaps even open up the much more important ethical discussion.

One is that

copyright law may be strong enough to override what they’re doing, similar to

what happened with Napster some twenty years ago. But his second point, that we

might figure out that these stronger LLMs are useful for a lot of things such

tech has been used for in the past, rather than the next step to artificial

general intelligence. That is, it’s not the birth of true AI, but simply a better

computing tool for certain kinds of analytical and tech work.

That gave me something cheerful to think about as I approached the New Year.

Nancy Jane Moore is the author of the fantasy novel For the Good of the Realm, the science fiction novel The Weave, and the novella Changeling, all from Aqueduct Press. Her short fiction has appeared in a number of anthologies and magazines and in a collection from PS Publishing. She holds a fourth degree black belt in Aikido. In other lifetimes she organized co-ops, practiced law, and worked as a legal editor. A native Anglo Texan, she lived in Washington, DC, for many years and now lives with her sweetheart in Oakland, California. Over the last few years, she has developed good relationships with her neighborhood crows. She is currently working on a sequel to For the Good of the Realm. Website (currently in progress): nancyjanemoore.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment