The Pleasures of Reading, Viewing, and Listening in 2017

by Kristi Carter

Entry into 2017 was surreal here in the Midwest. More record-breaking high temperatures for January didn’t mean there was any warmth for to be found as I toiled away on the last of my doctoral work indoors. I live in one of the reddest states in the US—a state famous to sociologists for its high ratio of interpartner violence when considering population distribution. A state where queer erasure is high despite the notorious murder of Brandon Teena.

As I closed the spine of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929) in the first week of January, my mind was churning sluggishly in an effort to reconcile the outcome of the election in November with these other confines on my life, on my body. The stasis of reflection that the page provided had never been more necessary, for listening and for creating.

While the books I describe here only make up a portion of what I read outside of editorial work, work with my students, and myriad stand-alone essays, stories, and poems, there is an inarguable thread linking these titles that rises to the surface more clearly than it has in past lists of what I’ve read over the course of a year. The thread sits dense, more like a black rope, each book a notch I’ve clung onto in an effort to climb out of the vacuum opening up beneath myself and those like me. As a feminist, trauma scholar, a person who identifies as a woman, and a poet, I’m no less than obsessed with the way that violence shapes the realities of those outside the dominion of power—and recursively, I have witnessed time and again how insidious and commonplace that violence becomes by the refusal to name it, to plant it down with a name among those it’s used against. For women, for people of color, for LGBTQIA+ members, for those outside the traditional conceptions of able-bodied, for the socioeconomically disadvantaged, the feminist tradition of naming thrives as a reflection of its crucial purposefulness against dismissal, gaslighting, and erasure.

Regardless of the validation from Woolf, my mind was still in a reeling state of numbness underscored by a constant fear that I would be blacklisted for my pansexuality. At work, my eyes would drift to the classroom door as my freshmen and I worked diligently on fine-tuning their academic writing skills. While my gender studies students civilly disagreed about abortion and celebrated passages from Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” my pride was watered down by anxiety that my authority was displaceable, literally removable. I was tired.

As a poet, the novel provides a place for me to surrender to capaciousness without losing (hopefully) the much beloved architecture of the written text. As Anne Carson put it last year in an interview in The Guardian “If prose is a house, poetry is a man on fire running quite fast through it.” Bogged down by the Foucauldian themes aforementioned, I needed to read something that would throw cold earth on my racing mind.

Sara Flannery Murphy’s novel, The Possessions and All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda both follow female protagonists through their attempts to unravel the disappearances of women in their lives. Murphy’s protagonist is a highly talented psychic empath whose ability to step into the mental realm of the deceased operates as a mirror to her own habits of avoiding and suppressing her own emotions. In comparison, Miranda’s plotline is more hard-boiled, following the cognitive dissonance of a likewise avoidant female protagonist whose personal mysteries are meted out in alternating timelines. The minds and bodies of women when focused on crimes against other women become unmoored, vicariously fragmented vehicles of power that destabilize their positions as upstanding members of society. In other words, confronting the problem makes these women frightening to those around them, as empowerment often will.

“Where is the line between empowerment and reproduction of patriarchal rituals?” I wrote in my journal as an undergrad. It’s a question that Marie Calloway (the author’s pen name) explores in her multimodal series of essays What purpose did I serve in your life (Tyrant Books, 2013). The book received press that focused on Calloway’s veiled identity and unabashedly graphic sex scenes, but no reviewer noted the division between author and narrator that inevitably serves as a part of art, no matter how biographical. As if Calloway has no power in showing us her vulnerable open body, as if she does not create the body again for us, with intentionality. That old refrain, a body of the marginalized is nothing more: a woman’s body is a woman’s body.

Poet Sheila McMullin in her debut collection daughterrarium (CSU Poetry Center 2017) smashes the reader over the head with a song that spits out those limiting beliefs. The second poem "Bad Woman, thought drawer variation" opens with raw use of language—a reclamation of the speaker’s trauma narrative in the mode of a stark factual account: "A boy sticks his dick in her ass and then in her vagina," and later in response to the doctor’s infantilizing comments (disguised as advice) while treating her for a subsequent infection, "I know how to wipe my ass.” The lightning bolt of recognition that ran through me reading this book reminds me my female body is contested in stasis, a weapon in motion.

Another preeminent theme McMullin works with is the relationship between mothers and daughters as a facet of understanding their own societal agency. Written about in depth by Marianne Hirsch in The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism (Indiana University Press, 1989), the feminist tradition of exploring the gendered conditioning of daughters functions as a way to disrupt the archetypal mother-daughter relationship in literature as one devoid of nuance and growth, a relationship in which replicas of the mother are produced ad infinitum as a function of the heteroreproductive imperative.

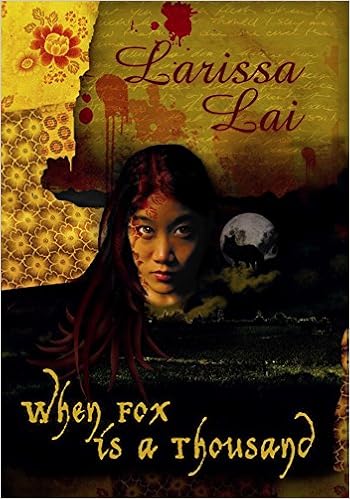

I’ve written about this trope, and my lived experience of it, a lot myself in my own poetry and scholarship. Myth and history rear up over and over in these narratives, one often threatening to eclipse the other, that power struggle a metaphor of purpose in the hands of the silenced whose access to fact is erased, stolen, or otherwise suppressed. Those relationships between women shine through in Larissa Lai’s When Fox is a Thousand (1995), wherein the blurring of ancient and contemporary timelines keenly illuminates the queer youth who are invisible in their adolescence and otherness, as well as the fox spirit who elects to remain invisible until she reanimates dead young women to commune with the living.

For those whose lives fall outside the privilege of the ‘norm,’ reality is already inherently surreal, incredible to those in power. Writers that take on this dimension of life through formal means that echo this displacement or by using realism as a means of holding up the unjust truth like a flawed jewel to the light, each flaw’s refraction a reminder of the larger problem. For these purposes, I have intentionally avoided the word “escape” throughout this piece, though it is referenced as one of the vestiges of recreational reading. Right now, that therapeutic method is not necessarily wrong, but even in a house not on fire, one must look squarely at those who live inside, at how they live, at how they don’t.

In January 2017, Orwell’s quintessential dystopian 1984 experienced a spike in sales so high the book was momentarily sold out on mass distributor Amazon. Who can forget the consummation of Winston and Julia’s lust in an illegal act of recreational sex?—or moreover, her prophetic pillow-talk afterward when she declares they will be caught and punished for their rebellion? Some are shaking their heads—it isn’t that dire—some are nodding. There is purpose to this caution and memory. As Lorde wrote in “Sister Outsider” (the poem that shares a title with her later, famous essay collection) which appears in the galvanizing and emboldening The Black Unicorn:

your light shines very brightly

but I want you

to know your darkness also

rich

and beyond fear. (1995)

In a time of “alternative facts” and “fake news” simply existing feels like a thoughtcrime, so we might as well think, and read, together, sharing the dark and the light.

------------------ A partial list of titles I read in 2017:

A Room of One's Own- Virginia Woolf (reprint by Martino Fine Books; April 4, 2012)

The Possessions - Sara Flannery Murphy (Harper; February 7, 2017)

All the Missing Girls - Megan Miranda (Simon & Schuster; Reprint edition January 31, 2017) What purpose did I serve in your life - Marie Calloway (Tyrant Books; June 4, 2013)

Eileen - Ottessa Moshfegh (Penguin Books; Reprint edition August 16, 2016) Comfort Woman - Nora Okja Keller (Penguin Books; reprint March 1, 1998)

My Name is Lucy Barton - Elizabeth Strout (Random House Trade Paperbacks; Reprint edition October 11, 2016)

Mother Love - Rita Dove (W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition May 17, 1996)

Edwin Mullhouse - Steven Millhauser (Vintage; Reprint edition April 16, 1996)

Hangsaman - Shirley Jackson (Penguin Classics; Reprint edition June 25, 2013)

The Hearing Trumpet - Lenora Carrington (Exact Change; February 2, 2004)

The Collector - John Fowles (Back Bay Books; Reprint edition August 4, 1997)

Giovanni's Room - James Baldwin (Vintage Books; reprint edition 2013)

Fun Home - Alison Bechdel (Mariner Books; Reprint edition June 5, 2007)

Lolita-Nabokov (Vintage; reprint 1989)

The Price of Salt-Patricia Highsmith (W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition 2004)

When fox is a thousand-Larissa Lai (reprint by Arsenal Pulp Press; September 1, 2004)

Hands That Break & Scar-Sarah Chavez (Sundress Publications, 2017)

Oranges are not the only fruit-Jeanette Winterson (Grove Press; August 20, 1997)

sad boy/detective-Sam Sax (Black Lawrence Press; September 28, 2015)

daughterrarium - Sheila McMullin (Cleveland State University Poetry Center; April 1, 2017)

The Black Unicorn - Audre Lorde (W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition August 17, 1995)

A Theory in Tears - Cassandra Troyan (Kenning Editions; 2016)

Other texts cited above:

“Anne Carson: 'I do not believe in art as therapy'” Anne Carson interviewed by Kate Kellaway. The Guardian. Oct 30, 2016.

The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism - Marianne Hirsch (Indiana University Press; Oct 22, 1989) “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” – Audre Lorde Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Crossing Press Feminist Series, 1997)

1984 – George Orwell (Penguin; 1949)

Kristi Carter’s poems have appeared in publications including

Alyss , Gertrude, So to Speak, poemmemoirstory (now

Nelle), CALYX, Nimrod, Naugatuck River Review, North

Carolina Literary Review, Not Somewhere Else But Here: A Contemporary

Anthology of Women and Place (Sundress Publications), and Hawaii Review

amongst others. Aqueduct recently published her narrative collection of poems, Cosmovore. In literature, art, and life,

she is deeply invested in depictions and subversions of motherhood (and

daughterhood), mother-daughter dynamics and tropes, sexual politics and

agencies, LGBTQ experiences, embodiment, memory, heritage, history, music,

myth, violence, and trauma.

No comments:

Post a Comment