Readings and Re-Readings, 2016

by Mark Rich

To give an example — to illustrate what I cannot explain:

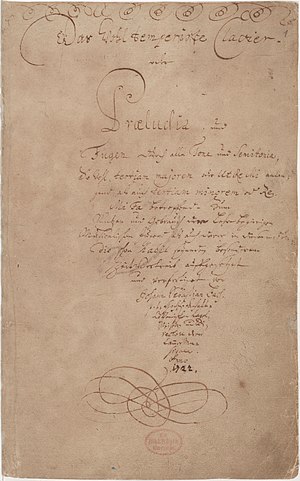

A few evenings ago, after reading Bach's prelude No. 11, I thought I should read it again, start to end. "I was getting ahold of it," goes the antiquated phrase. "Getting ahold of," though, I keep rear-stage as motivating reason for reading Bach's preludes and fugues: because my effort, very nearly a nightly one for almost a year, arises from the fact that I have always been a poor reader. Have you ever had one regret about your lack of learning and application? Count yourself lucky — says one who would be a mathematical whiz-kid, could he count half such, in his life. Yet by happenstance this particular lack has risen to the fore.

My little essay has to do with this — which ties in to other failures we shall sweep rugwards; it involves books and Bach; and it introduces a pair who have become regulars in Martha's and my household, who are rescue Scottiedogs: Callie, a small wheaten, and Hutton, a more typical black-haired one, who sits at the Scottie weight-scale's other end.

In reading prelude No. 11, I played piano. (A writer generally cannot afford a piano; but when a kind old gent has a piano but gives it up, along with everything else, at auction, a scant dozens of yards from the writer's home, the writer has a faint chance at owning what cannot be afforded.) Yet I played not only on piano but on Scottiedog sensibilities. During the first run-through, in the background I heard runnings, growlings, barkings, and squeak-toy squeakings. Pause. Quiet. Then, reading the prelude again, I heard dashings, snarlings, clashings, and squawk-toy squawkings. You may not know that No. 11 ranks below the most complex, among the preludes — yet not at bottom, by any means. Having read it twice, I went on to the fugue — and played only piano, since the prelude had finished off the Scots. Later I headed to the kitchen, stepping to avoid keeled-over forms. Martha said, "I thought we had ten Scotties. But maybe you didn't notice."

I do notice, to some degree. My attention stays locked on Bach as far as possible, though. My remedy for past shortcomings — my nightly reading of a prelude and fugue, from prelude No. 1 to fugue No. 24 without backtracking — I take in, like snake oil from a lovely little bottle, to cure my reading ailment. Bach offers complicated pieces in all key signatures; and by not studying these works — which once I supposedly did, in foolish college days — but rather by simply reading, I daily receive my due, as a bad boy. (Bad boys, you may know, relish telling about whippings.)

"Tradition, like charity, begins at home. You can only reach the background through the foreground." These paired thoughts, from Van Wyck Brooks, ring true for me in this moment when I am thinking about Scotties who react to Bach — and who, if they have endured an under-stimulating day, react to him the way its first audience did to

The Rite of Spring. I was reading Brooks's

New England: Indian Summer during a period when I was also finishing

The Education of Henry Adams, James Russell Lowell's

The Vision of Sir Launfal and Other Poems, John Fiske's

The Destiny of Man, and Thomas Bailey Aldrich's

The Story of a Bad Boy; and how marvelous Brooks is, in this volume, illuminating lives and works including these that I mention.

Indian Summer had special force, for me, after reading Adams, whose memoir is strangely intense and magnificently thoughtful. I would love to lose myself again in its pages. As well as in that Brooks volume.

Brooks, in Aldrich, sees the first flow of the flood that would arrive, of novels about growing up — which in our day sometimes parade as memoirs, as though with that name they might be more true. He notes that Aldrich had a rare virtue. He knew when to stop. You must read

Bad Boy, to know how true this is.

The boy in Aldrich received no whipping more severe, as I recall, than being exploded, by fireworks. I have no notes as to his wording; but "being exploded" comes to mind as appropriate and correct, just as does "whippings," for my Bach reading: for I am bad, old boy, returned late to the exercise, who must be whipped by it. And who must whip up a pair of Scots, fifteen and twenty-five pounds, thereby. Bach does proves to be hard on our century-old maple floors. But as to that, what cares has one who is poised to spy the next flat, sharp, or double-sharp that might express a movement in Bach's thought-stream?

To read Aldrich startled me, with its narrative felicities. To read Stevenson's

Child's Garden of Verses — end to end, which I never happened to do before — delighted me. To finally read Koestler's

Darkness at Noon may not have been transformative; but it roared at me. Other books made noises in my soul, including smallish ones, such as

Winnie-the-Pooh, Stuart Little, Peter Pan, Baum's

Queen Zixi of Ix, and Katherine Milhous's

Colonel Keeperupper; mid-sizers such as Carolyn Keene's

The Mystery of the Old Clock and Chinua Achebe's

No Longer at Ease; and fuller volumes, mostly fiction: collections of Conan Doyle and Dickens stories, Verne's

A Special Correspondent and

Hector Servadac, Goldsmith's

The Vicar of Wakefield, Muriel Spark's

Robinson. And books in which Christopher Hobhouse writes on the Crystal Palace, and Jill Jonnes, on the Eiffel Tower.

I read two Brooks books, this year, with

Indian Summer being the transformative one, in the sense that my understanding of the period from the later 1800s into the early 1900s in American cultural history will never be the same as before: it cannot be. At some point I need to read all Brooks, volume to volume, sequentially, as I am reading Bach. I hope to reach that point: for Brooks reached his perspective and perceptions by immersing himself in American literature to the point, it seems, of literal madness. His dedication, which sent him to an asylum for a time, must have been akin to the one that provoked Bach into producing the cycle of preludes and fugues that he offered to the world as music that not only gives aesthetic pleasure but makes a case for equally "tempering" notes in the musical scale.

Evidence that it is a musical argument appears, for instance, in No. 8, which has daunted me now twelve or more times, this year. For how better might Bach have made his point than by writing the prelude in six flats, and then the fugue, in six sharps? In other words, e-flat minor, then d-sharp minor. I enjoy, in reading all except No. 8, the fact that I warm my mind to a key signature during the prelude: this makes it more likely that I will comfortably read the fugue. So imagine how it feels, especially when one has forgotten that No. 8 is The One, when after reading four pages in which one has become habituated to transforming the staff's notes to flats, one turns the page to the second part, in which one must suddenly transform them to sharps.

I will say that I have, a few times, made the transition, and suffered through mental gymnastics upon the whipping bench long enough, to actually read both prelude and fugue, No. 8, in one sitting. Bach made No. 8 especially intimidating by keeping up the counterpoint for eight pages. Imagine how Martha suffered, during my read-through last January: eight pages of fugue, and probably eight hundred minutes of me trying to read sharps when the notes kept wanting, in my head, to revert to flats. By the time we had adopted our new musically inclined rescues, fortunately, I had subjected Martha to this several more times, and so presumably was more adept at administering torture.

Not all present-day Bach readers, by the way, have this pleasure: for Busoni and perhaps others made early transcriptions, and published both prelude and fugue with the same key-signature. Those readers, though, can never truly and viscerally appreciate Bach's madness-level.

The more powerful are Bach's harmonic expressions, the more powerfully seem Scottiedog neural connections to be stimulated. As I recall, I first noticed the Scots reacting extremely to Bach during the final fugue in the edition I have at hand. Fugue No. 24 has majestic scope, thoughtfulness, complication, and length — everything that gives pause to the pianist. (The harpsichordist that I more or less was, in college years, never moved past that pause.) By this point in the year, I was reading No. 24 with a fair mockery of competency; and the Scots went into throes, paroxysms, and conniption fits — being exploded, before the end, by the harmonic complexities Bach ever-so-casually trots out, here and there — as though he had inklings, that devil, that Scots loomed in the future, as interactive audiences and musical assistants to bad, old boys.

When we first moved to western Wisconsin, on the nights when Martha cooked supper, I usually retreated to a rocking chair for some on-going reading, from one or other old, cloth-bound book. This would fall after the late-afternoon happy hour. With Martha these days being regularly the supper cook, for nearly a year now, with a flew glasses of elevation, or perhaps delirium, in my system, I have sat at the piano.

You might suggest, knowing this, that the Scots might be reacting to wafting intimations of dishes and dinners, and not dissonant-consonant-consummate Bach. Consider this, then. Our piano sits insulated from the Scots' running spaces through the house — not due to forethought, but to the accident that we are antique dealers who have Really Too Much. I had grown accustomed to the Scots being exploded, by later spring or early summer — and to Callie, the wheaten, making an attempt to get past the Really Too Much. Something like a plastic bucket full of doorknobs and glass insulators held up a 1960s plastic child's record-player; and for a week or so, as I recall, Callie would manage to climb atop the blue plastic case, to watch me play while expressing with various throttled, thweeping noises her excitement.

You will recall that this is an essay about reading.

One evening she finessed her way onto and then beyond the blue case. Boxes sat piled beside the piano, packed with brass hose nozzles, paper valentines, shoehorns, plastic horses, or sadirons — who knows what, really. Somehow the boxes' arrangement allowed a fifteen-pounder to climb to keyboard-level. Her madness-level, it may be. While noting this change in circumstances, I went on with my reading, having the sort of dedication that leads somewhere.

From her new elevation, our wheaten stepped to the piano's bass-note keys, producing a "tone cluster" — so-called by pianists just before they, with knowing glances, invoke John Cage. (I recall having seen Peter Schickele use them: so tone clusters have come within laughing distance of Bach before.) I doubt I was making any sense of my evening reading (as you will recall, this is about —— ) by the time Callie made a second tone cluster, with her next paw. Then, on the ivories all-fours, she walked, not quite pranced, to the upper notes. She turned her head to look at me, happy with herself, her improvisation, or with my breakdown — not nervous, luckily. She then proved how much smaller she is than we thought she was, by turning around — on those pale-celluloid and blackened-wood keys — effortlessly, without the least sign that we had not adopted a toy mountain goat. Then she descended to the bass notes again, tone-cluster by tone-cluster by barrumph. (A term not in common use, as yet, among pianists.)

With this lovely cadenza she ended my reading, that evening.

Mark Rich is the author of a major biographical and critical study,

C.M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary, published by McFarland. He has had two collections of short fiction published —

Edge of Our Lives (RedJack) and

Across the Sky

(Fairwood) — as well as chapbooks from presses including Gothic and

Small Beer. With partner-in-life Martha and Scotties-in-life Callie and Hutton, he

lives in the Coulee region of Wisconsin where an early-1900s house, a

collection of dilapidated antique furniture, and a large garden

preoccupy him with their needs. He frequently contributes essays to

The New York Review of Science Fiction and

The Cascadia Subduction Zone.