Thursday, January 31, 2008

Safety in Public Spaces

There's no doubt the harassment women face in public spaces needs to be addressed - whether it is on the street, the train, or even the internet. We've been subjected to regular catcalls and groping for far too long. But while the idea of a safe space is compelling, this international trend - which often comes couched in paternalistic rhetoric about "protecting" women - raises questions of just how equal the sexes are if women's safety relies on us being separated. After all, shouldn't we be targeting the gropers and harassers? The onus should be on men to stop harassing women, not on women to escape them.

Betsy Eudey, director of gender studies at California State University, says that while some single-sex environments could be beneficial - locker rooms where people are expected to be naked are an obvious example - she finds that "segregated spaces only enhance division by sex, and prevent the necessary actions needed to make public spaces safe and welcoming to all".

And then she notes that

Katha Pollitt, in an interview for this article, said that she doesn't think that the rise of women-only spaces will excuse society from confronting harassment and violence, but instead offer a small respite for women in a male-dominated world.

"Obviously, there would never be enough women-only space to accommodate all women all the time - half the subway cars or half the hotels…Women-only space is just a little breathing place for a few women every now and then."

Valenti, however, wonders whether women will be blamed for their harassment when they chose not to use the "safe" space provided.

I have some ideas on this subject myself (qv, for instance, a certain scene in Stretto), but I'm more interested in hearing how the issue strikes you-all.

Monday, January 28, 2008

That coward thing

“Mr. Dear, you frankly are a phony,” Svet said. “You preach nonviolence but you are the same man who took a hammer and a can of paint against a U.S. aircraft.”

As I recall, the activists who have wielded hammers and red paint against bombers do not actually damage the aircraft but rather do so to make a symbolic statement. The judge, apparently, is an ignoramus without any knowledge (much less understanding) of nonviolent activism: this explains his telling Dear that "you frankly are a phony," and his saying that Dear is "no Gandi."

But the charge of cowardice? That's what I don't get. It sounds illogical and irrational on its face.

Here in the US, we hear people labeled "cowards" by the media and government officials all the time. In some cases, the people so labeled are murderers or terrorists. I don't quite get the logic of that particular application of the characterization, except that for a simplistic notion that all Good Guys are heroes and all Bad Guys are cowards. But I really scratch my head when time and again the people so labeled are those who have had the temerity to stand up to the school-yard bully knowing that in doing so they've risked getting beaten to a pulp. In this case, on the one side---Judge Svet's side---we have a government that made more than 900 "false statements" (i.e., they told conscious lies) to justify devastating the lives and culture of several million people. On the other side, we have Dear's Pax Christi group, saying that that destruction and devastation is unjust and morally unacceptable. For me, allying oneself with the lying bully is the real act of cowardice.

I'm wondering: is it a "manliness" issue? I gather from Nussbaum's piece that John Wayne is now the exemplar for manliness. (Perceptions of gender just keep changing and changing, don't they...) Since the days of the Reagan Administration I've had it firmly in mind that the image of John Wayne (channeled through Ronald Reagan)---the man's man of a hero---is that of a thuggish bully who rides roughshod over everyone who gets in his way. Is it possible that people now think that the bully is the manly hero and anyone who thumbs their nose at the bully is, by definition, "unmanly"? Am I leaping to conclusions? Such reasoning doesn't square with the way the word "coward" was used when I was growing up, but as I've noted elsewhere, anything to do with gender is riddled with discursive instability. I wonder if the judge thinks that the nuns arrested for hitting the bomber with a hammer are cowards, too? Or do people who use the word in that way see it as applicable to men only?

It's a mystery-- to me, anyway. If anyone has any ideas about this, pray do enlighten me.

Dancing along the Aqueduct

Friday, January 25, 2008

Julie Phillips on Boys' Liberation & Other Stuff

She writes in an email to me:

I was going to send you an intro to my piece about The Dangerous Book for Boys, wasn’t I? I was looking at the people who’ve already weighed in on your blog. People are so good, they do their assignments right, they come up with useful stuff…

So I feel like I should add a couple of proper recommendations. One book that I really enjoyed last fall is the new Jeanette Winterson, The Stone Gods, which is already out in the UK and is coming out in the US in April. Its science fiction elements are not always all that strong or original (though I liked the robot sex), but it’s very angry and very funny, always a good combination.

And do you have books that have been sitting on your shelves, surrounded by a halo of respect and affection, for so long that you can’t remember what it was that you loved about them? I took down and reread an old Seal Press book, Tove Ditlevsen’s Early Spring, the other day, and now I remember what I loved about it. It’s by a poet who grew up in the slums of Copenhagen during the Depression, enduring miserable poverty and equally miserable parents, and what I enjoy and admire is the clarity with which she’s able to look back at herself and her surroundings. She writes with a funny kind of dispassionate understanding, with anger (and of course humor) boiling just under it. It’s the best book I know about a writer’s childhood.

It’s short, and you can order it on Amazon for 25 cents. Have you ever read it? You would like it.

Anyway, about my piece on The Dangerous Book for Boys, the only intro it really needs is that it’s partly a review of the Dutch/Flemish edition, and I wrote it for a local audience, so I found myself making all kinds of Dutch references, especially to the Dutch ambivalence about history. The Dutch feel uncomfortable teaching their own history. They associate it with national pride (which they don’t like: it reminds them too much of Nazi Germany). And they don’t like to look at the negative parts of their own colonial past. Now that they’re confronted with a large immigrant group, they don’t know what to do. Should immigrants be expected to care about Dutch history? If they don’t learn it, can they integrate into Dutch culture?

The essay is also about superheroes, pink toys, and why girls want to be librarians. In retrospect I think I made too much of an effort to respect this whole “boys will be boys” business, which I would like to think is, as one male friend of mine put it, just a “reactionary last gasp.” But I am a woman and don’t like to look less than understanding. It’s here

What has really put me off the boys’ liberation movement is a book called “Manliness,” in which “natural” male qualities are shown “naturally” to lead to sexism and George W. Bush. I wrote about that too, here.

Actually, the very best thing I’ve read lately is Martha C. Nussbaum’s review of “Manliness” in The New Republic. It’s online here. She takes the book and its author apart with a serene authority that’s a pleasure to see.

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

"Trying to Say Something True"

In his intro to the interview, Josh writes:

For all that Herb Philbrick led three lives, the indefatigable Horace Chandler Davis puts him to shame, leading at least seven. He is Chan Davis, the writer of a dozen science fiction stories that probe deeply into social and ethical issues; he is the renowned mathematician Chandler Davis, longtime editor of The Mathematical Intelligencer and innovator in the theory of operators and matrices; he is an anti-war activist, having coordinated international protests against the war in Vietnam and been a director of Science for Peace; he is a composer, having cowritten the music for Theodore Sturgeon's song "Thunder and Roses" as well as more recent works; he is a member of the mighty intellectual family that includes his wife, the historian Natalie Zemon Davis, and his daughter, the literary and cultural critic Simone Weil Davis; he is the author of several acclaimed poems; and he is a lifelong civil libertarian who has organized for freedom of expression in Eastern Europe as well as North America.

In 1953, Chandler Davis was served with a subpoena as a result of his having paid for the printing of a pamphlet critical of HUAC. His subsequent ordeal included the loss of his job at the University of Michigan and a six-month imprisonment in 1960 for contempt of Congress. Blacklisted from full-time academic jobs in the US, he ultimately found employment at the University of Toronto in 1962, where he continues to work as Emeritus Professor of Mathematics. He and his wife have each written articles and given lectures recounting his case in the context of the Red Scare years.

Check it out!Sunday, January 13, 2008

Dozois's Year's Best Anthology

Tuesday, January 8, 2008

Get Your Aqueduct Gazette Here

ETA: We've scaled down the resolution of the pdf file so that it's a more manageable download. Sorry about any frustration or inconvenience the original version might have caused you.

Monday, January 7, 2008

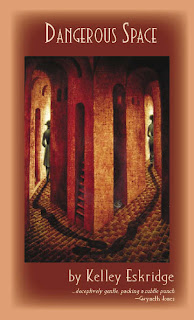

Dangerous Stuff

In his blurb for Dangerous Space, Matt Ruff says,

It takes a special talent to write about emotions this raw without embarrassing yourself.

Kelley Eskridge does not embarrass herself in the slightest. This is a superb collection of short stories.

Sunday, January 6, 2008

Filter House by Nisi Shawl

Nisi has published before with Aqueduct: she's the author, with Cynthia Ward, of the acclaimed Writing the Other: A Practical Approach, Vol. 8 in the Conversation Pieces series.