by Susan W. Lyons

Yes, it’s a strange time. In fact, it’s a strange spacetime in a stranger universe (or multiverse, if you’re into that sort of thing). Fortunately, Robert B. Crease and Alfred Scharff Goldhaber offer friendly guidance for those of us who like our physics without all that messy mathiness. The Quantum Moment (W.W. Norton and Company, 2014) does not explain Trumpery, but it does suggest that a queasy uncertainty about what constitutes normality is—well—normal, given the realization that foundational classical physics does not account for the discovery that energy comes in packets (quanta). The “Newtonian Moment” suggests a world ruled by “causality, consistency, and continuity” (21), but the “Quantum Moment” is “murkier and more unsettled” (25). If you’ve ever wondered why reality seems so fractured or why wicked Walter White from Breaking Bad chooses “Heisenberg” as his nom de guerre, this is the book for you.

Nastiness and venality happen to be the fictional subjects of the Australian television series Rake (Essential Media and Entertainment, ABC1, 2010). If I tell you that the hero of the series is a Sydney barrister by the name of Cleaver Greene who enthusiastically defends some of greediest and guiltiest clients available, you’ll wonder, “Why bother? If I want greed and guilt all I have to do is read the paper or plug into my news podcast.” But I’ll add that Greene is also an idealist and a romantic with one of the wittiest and most eloquent voices since Sir John Falstaff. Brilliantly played by Richard Roxburgh, Greene manages to slink his way through the roughest trials inside and outside the courtroom with a cynical smile and just the right bon mot. The juiciest villains, naturally, are not Greene’s clients but the judges and politicians who determine their prosecution and fates: the ones who play outsized power games, presciently as it happens, since the series first aired in 2010.

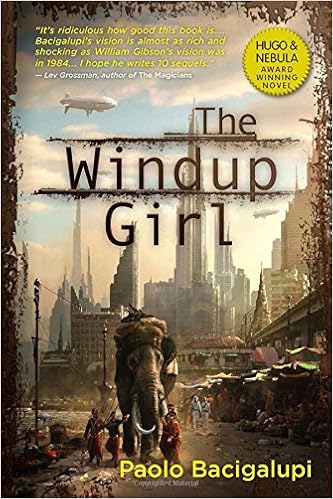

2017 seems to be a year we read, view, and listen through a dystopian filter, and Paolo Bacigalupi’s Windup Girl (Nightshade Books, 2010) shows us just how dark and dirty that filter can be, particularly in terms of gender, race, sexuality, and what it means to be “natural” or “human” in a Thailand set two hundred years in the future, where American genetic-engineering companies use calories as currency. Ecocritics will find this book, winner of the 2010 Nebula award, brilliant. I admire the world-building without wanting to venture further into its forbidding speculations.

Instead, I am indulging my passion for Margaret Atwood’s worlds, where genetic engineering and corporate greed are as dismaying and dystopian as Bacigalupi’s, but where energetic and sprightly characters prevail in even the most daunting circumstances. As I’m writing this, having not quite finished The Heart Goes Last (Doubleday, 2015), I’m hoping Charmaine and Stan—with the help of a crop of Green Men, a troupe of Elvises, and a Marilyn who is the love slave of a blue knitted teddy bear—will eventually reunite after their separate exits from the for-profit prison called Positron Project in the Town of Consilience in a place somewhere in Rustbelt, U.S.A.

And then there’s Atwood’s graphic novel Angel Catbird (Dark Horse Comics, 2016), the illustrator of which has the wonderfully improbable name of Johnnie Christmas. Angel Catbird is cosponsored by the Canadian Conservancy’s initiative to Keep Cats Safe and Save Birds’ Lives. Trust me: in this story about another world of genetic engineering gone awry, keeping your cats inside the house is the best way to prevent them from becoming mutants.

And finally, there are the hysterically funny and sometimes just plain hysterical doings of Jimmy, Amanda, Glenn, and the rest of the characters of the MaddAddams trilogy (McClelland and Stewart: Oryx and Crake, 2003; The Year of the Flood, 2009; MaddAddams, 2013). In this dark world of genetically-engineered hybrids (ChickieNobs, anyone?) and postapocalyptic ecological disaster, the future may well rest with the gentle post-human Crakers, who turn blue when they’re in heat and travel in herds.

As to the pleasures of listening in 2017, you can hear Pamela Bedore speak more about the perils of environmental dystopias in Great Utopian and Dystopian Works of Literature (Great Courses, 2017). In this series of lectures ranging from Utopia to The Walking Dead, you’ll also find provocative and entertaining insights into the speculative worlds of Atwood, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler, and Suzanne Collins. Bedore, an Associate Professor of English at the University of Connecticut, publishes extensively on popular culture, rhetoric, and genre fiction.

Speaking of The Walking Dead, I hear there are more near-future Congressional discussions about “reproductive rights” and “protecting the homeland.”

I think I’ll reread The Handmaid’s Tale.

Susan W. Lyons worked at the Avery Point campus of the University of Connecticut for over twenty years teaching courses in writing and literature and, later, directing Academic Services, where she coordinated curriculum, scheduling, and academic support in writing, literature, history, math, chemistry, biology, and physics. She lives in East Lyme, Connecticut. Aqueduct published her debut novel, Time's Oldest Daughter, earlier this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment