Readings & Echoes, 2023: Two Notes

by Mark Rich

First Note

"The boy had heard once that some people had so many books that they only read each book once."

It was only last night, as I write this, that I happened on this line.

And how happy I was, that I read these words while actually re-reading that particular book!

I read it when quite young — although the echoes in my mind of the scenes as they progress are so clear, sometimes, that I begin to suspect this is not my first re-reading.

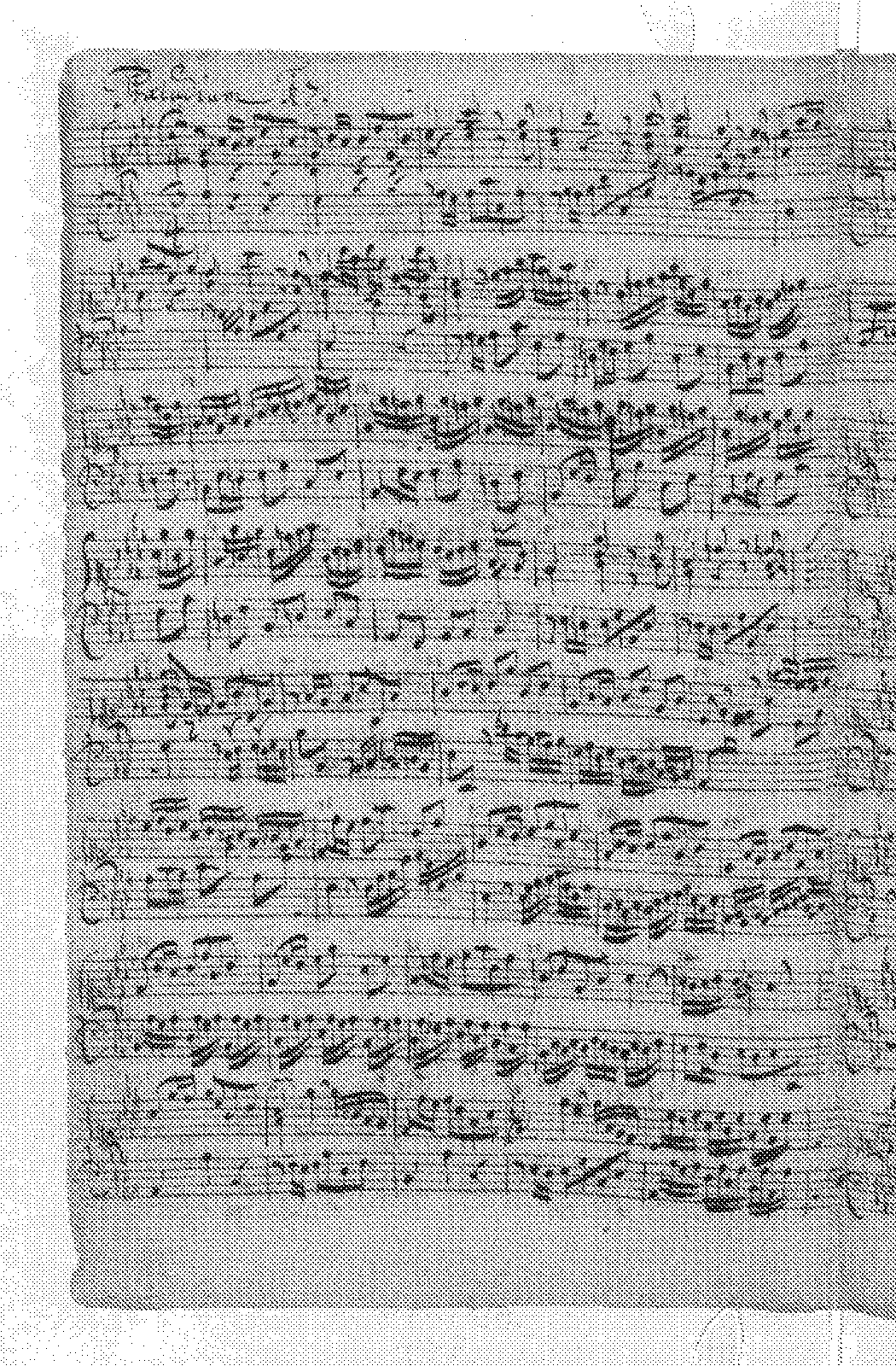

I have been thinking about those echoes partly because of J.S. Bach. The other day I was page-scrutinizing one of the fugues I have memorized, being curious if the restatements of the theme saw modification through the course of the piece, or if they cleaved to the lineaments of the original statement. It turns out that Bach, in Book II Fugue 17, restates his original theme, which takes a question-and-answer form. When he moves it up or down in the scale, he accommodates the scale but retains the lineaments. The musical context, along the way, bows to the theme, not vice-versa.

This surprised me, since the musical effect is one of great exploration and variation. Most of that occurs around the theme — above, below, and in the trailing-along after-phrases. The theme itself appears as statement and restatement, then slightly altered statement which is itself restated, then restatement.

The ear reacts to the iterations positively, thanks to that precision in their character.You might think the world would value the fantasia or musical fantasy above the fugue, for by its very nature the fantasy must show a constant level of invention and cannot rely upon a structure of strict reiterations. Yet the fugue tends to win higher regard.

Wm. Armstrong, who wrote Sounder, the book I am re-reading, states in a prologue that it is not his story that he is telling. It belonged to an old black man whose personal story it apparently was. For Armstrong, the act of composition was in itself the act of echoing.

Each act of reading, then, adds a reverberation, or a new echo in the reader's soul.

The copy that I am now reading I picked up at a thrift store. Yesterday I came across the prior owner's bookmark, a folded-up foil inner wrapper from a famous-name chocolate which is, to me, worthless stuff, being mainly sugar. This placemark was around page 32 or so. I suspect the prior owner gave up reading the book around there, because the book has so little sugar in it.

So very little, in fact, that I like it greatly.

Second Note

The boy should have heard, too, that some people have so many books that they only hope to open each book at least once.

This spring or summer, Martha and I were in a valley thrift store that opens two Saturday per month. I had already scouted through the closet where books are shelved, but in coming back from looking at kitchenware in the basement found Martha there. She held out a book. "Don't you want this one?"

I did, although I figured it would go into the pile of books to read sometime or never. Last year I re-read Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, however; and because of my interest in that cusp period in the early 1950s when Galaxy magazine seemed to be transforming the field, it had become a small goal to dig out the issue, buried somewhere in those sometime-or-never piles, that contained "The Fireman," the Galaxy story that became the famous novel.

This book Martha dug up, though, was a Bradbury collection: A Pleasure To Burn: Fahrenheit 451 Stories, published in paperback in 2011. It includes "The Fireman." Out of curiosity one day, I read the first story in the anthology, which purports to contain sixteen works that prefigure the novel. In a way that some Bradbury stories can, this story both dissatisfied and refreshed me. The notions of books and of burning played into it. They play into nearly all the stories here; and then they numb the reader who persists through the novellas that presumably are both pre-envisionings of the Montag-quest novel: "Long After Midnight" and "The Fireman." I emerged from the anthology, after many bedtime readings, having the clear sense that I had read a half-dozen tales that followed Montag and his fellow characters. But apparently there are just these two.

Have you ever read Bradbury's Surround Yourself with Your Loves and Live Forever? In 2008, through the efforts of John L. Coker, III, editor and publisher, it brought together seven accounts by Bradbury of his pivotal and literally galvanizing youthful meeting with "Mr. Electrico." While nothing might seem less enticing than a collection of stories each of which tell the same story, I found this sequence of tales fascinating in the way that waves on a beach are fascinating. Each one has its own claim to existence; no two are alike.

I am not sure I would recommend A Pleasure To Burn as highly as Surround Yourself. Yet it offers a window into Bradbury's soul that does not diminish it, in the way some windows can.

I say this because I clearly recall the point when, in my teens, I gave up reading Bradbury. In one of his seemingly endless R Is for Ray and B Is for Bradbury anthologies in the 1970s, I came across a story I had read before, in another of these Bantam collections. I read it again anyway, only to find that here it had a different ending. I felt as though I had caught Bradbury stealing from himself, and then trying to hide the fact.

Apparently I was responding to echoes and reiterations even then. How would I respond to those stories, which were the same except in their endings, today? I am not sure. In A Pleasure To Burn, in contrast, I came to feel the struggle that must have stirred in Bradbury, between the themes that obsessed him, that insisted on rearing their heads in his work time and again, and the contrary striving he felt toward the new. In a sense his work yearned itself toward the fugue while he himself yearned toward the fantasy.

I am cutting this short due to this week's health and time constraints, but think I can close on a note that may ring nearer the hearts of some Aqueduct stalwarts.

At another thrift shop I found a book I expected to just price and try to sell for a few dollars: Karenna Gore Schiff's Lighting the Way: Nine Women Who Changed Modern America. I still expect to do that. One afternoon, though, I idly picked it up and looked at the contents and thought to myself that I really should know more than I do about at least three of the book's subjects — Ida B. Wells, Mother Jones, and Frances Perkins. I have gotten as far as Mother Jones, so far. Schiff's book is clearly stated and seemingly reliable in its sources; is a good, solid effort, admirable and useful.

I should have known beforehand that Mother Jones's great issue was child labor. Now I do.

I have a fat old paperback, an Oscar Williams-edited poetry anthology that I have been perusing nightly, more or less randomly. One afternoon during the week I was reading Schiff more actively, I had the brilliant notion to look at Williams's contents pages and see what poets exactly were included. Coming across the name Sarah N. Cleghorn, I had the inevitable jerk of the knee: "Who the hell is — ?"

I went instantly to her page, and her quite short verse — which must have been touched by Mother Jones.

The Golf Links

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.

It was more likely touched, I should say, by the echoes of Mother Jones. (And the verse has no sugar! I like it.)

— Cashton, Wisconsin, 13 & 15 December 2023

Mark Rich has had two collections of short fiction published — Edge of Our Lives (RedJack) and Across the Sky (Fairwood) — as well as chapbooks from presses including Gothic and Small Beer. He is also the author of a major biographical and critical study, C.M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary, published by McFarland and, most recently, of Toys in the Age of Wonder: Science Fiction, Society and the Symbolism of Play. His poems have recently appeared in The Lyric, Penumbric, British Fantasy Society's Horizons, and Blue Unicorn. He lives in Cashton, Wisconsin, with partner-in-life Martha Borchardt and two partners-in-happy-hours Scottie dogs.

No comments:

Post a Comment