Bears. Beets. Battlestar Galactica. Beowulf.

(with apologies to “The Office”)

by Kate Boyes

I began 2020 resolved to give away most of my stash of quilting fabric because there was no way I could use it all in one lifetime. Ditto for the stacks of Portuguese cotton flannel sheets I'd purchased at garage sales over the years. I remember feeling terribly virtuous in late February when, after weeks of sorting and deliberation, I had a row of sacks packed full of fabric and sheets ready to donate.

Reading The Bear, by Andrew Krivak, kept my resolve strong during the culling process. There are few mass-produced objects remaining in the world Krivak creates, a world that feels like it could be a future version of ours, and those objects cause more sorrow than joy. Two of the main characters, a father and his young daughter, make, gather, or grow anything they need. The story is moving and magical, and Krivak's words cut straight to my heart. But way back in early 2020, I honed in on the theme of living simply and in harmony with nature, a focus so narrow I am embarrassed to admit it now. I didn't know this was the last book I would read for almost half a year, and the first one I would pick up when I returned to reading.

The sacks never made it to the thrift store. On my final trip to town before the lockdown (I didn't go to town again for eight months), the thrift store was closed. A few days later, the health care community began requesting donations of cloth face masks. This was in March, when a dozen ads for masks didn't pop up every time we opened Facebook, when hand-made was the only type available. Then family members who are medical frontline and other essential workers asked me to make masks for them. The face coverings needed to be sewn from tightly woven fabric, like the kind used for quilting, and lined with something soft, like flannel. I was on it.

Thus began my months of sewing during the day and watching something—anything—in the evening to block out, briefly, thoughts of the unfolding disaster. Those months are a bit of a blur, but bright moments stand out. The soundtrack from Harriet, played on repeat and accompanied by the sharp staccato of the sewing machine. Sir Patrick Stewart reading sonnets, and giving his character, Jean-Luc, vulnerability and new layers of depth in Picard. J. K. Simmons playing the heck out of his role(s) of a lifetime in Counterpart. Jordan Peele's The Twilight Zone—Peele updates the best elements of the original series, shows us what it means to take inclusivity seriously, and does not tiptoe around the oozing sores of our painfully imperfect society. Tales from the Loop—oddly fascinating, although it left me with ??????s. The music of Amy Wedge, especially her songs for Keeping Faith, a Welsh TV series. The Vast of Night: my favorite movie of the year; a breathless, sometimes frenetic, sometimes eerily calm, beautifully filmed story about what happens in a small town on the night of an important basketball game when two teens discover there is another, possibly cosmic, game afoot.

Much of my pleasurable viewing and listening during the first half of the year involved the natural environment. I noticed unusual happenings in the yard and forest around my home soon after the first lockdown began, when there were rumors of cats and dogs becoming infected by It—i.e., the-disease-that-shall-not-be-named (because the gods, who most certainly have gone crazy, might be listening)—and passing It to their human overlords. Folks kept their pets indoors, and the amount of bird calls and songs increased immediately. A rufous-sided towhee began sitting on my doorstep, squawking in rhythm with the sewing machine. The doe who brings one fawn with her every year to graze in the garden showed up with twins, then a second doe came to nosh with her three wobbly-legged fawns: I had never seen a doe with triplets before (fortunately, ten times the usual number of beets had been planted in anticipation of food shortages; the deer enjoyed them). Squirrels spiraled up and around shore pines in elaborate games of chase. Rabbits hopped out from their hiding places under the salal to nibble dandelions. Disney could have shot scenes for a live-action Bambi out there.

Activity outside increased after dark, too, when bears emerged from the forest. They've visited before, but never for long because they're usually hounded away quickly by, well, hounds. This year they hung around. Wide awake in bed, my head filled with pandemic worries, I could hear them grumbling around the place. Knocking over neat rows of stacked firewood to catch mice. Digging into the compost bin, and then relocating the bin to odd sections of the yard (some day, if I achieve enlightenment, I will comprehend this). Once, years ago, I left the shed door open, and a bear ate—plastic bag and all—a sack of garbage I had stored inside. That story must be part of forest lore now, because every bear who visited seemed convinced that the shed door would open if only it was banged on a little harder or for a little longer.

For me, the year was split down the middle into very different halves: before I was sick/after I was sick. Between those were a few dark weeks in July when I had a high and lingering fever, a headache, intense fatigue, and an incapacitating sense of dread. I did not have It, but I thought I did. When I found out my illness was 'only' salmonella poisoning (caused by a store-bought onion), I stood up, did a shaky happy dance, then went back to sleep.

I emerged from the fever underworld with three directives: re-read The Bear, plant more beets (which I did at once), and spend time with Beowulf. I have no idea where that last directive came from, so I can offer no explanation. In a year during which I took extraordinary precautions to avoid a deadly pandemic but was almost killed by an onion, I'm not sure explanations are necessary (my nomination for the 2020 theme song goes to Talking Heads' “Stop Making Sense”). I had time to read because I was no longer sewing face masks: they were available from a zillion companies at that point, and I had only a quart-size baggie full of scraps left from all those sacks of fabric and sheets I had planned to donate back in February.

On my second pass through The Bear, I realized it is the one book that I needed—absolutely—to read this year. It left me feeling grateful for the tenuous and brief connections we have with each other and with the world, and it led me, very gently, to a place where I felt at peace about letting go of those connections if necessary. I was quiet and calm when I finished the book. I recommend it.

I'd read Beowulf before, but I approached my deep dive into the story this year as if it were a game, the sport of sussing out what the translations, interpretations, and presentations of the story—over 1,000+ years; across cultures; under the influence of various religions; by people with vastly different backgrounds, sensibilities, and goals—say about myth, history, and Beowulfian fandom. I'll spare you my analysis, but I will mention a few of my favorite sources because most of my listening, viewing, and reading pleasures in the second half of 2020 were related to Beowulf.

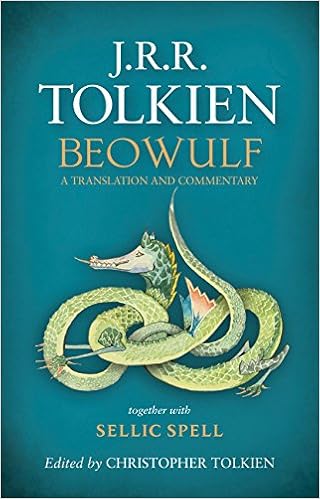

I eased in by watching the 2007 movie, which takes liberties with the story but is great fun—Angelina Jolie totally rocks her role as Grendel's mother. Although I'm not one to stop reading a book once I start, there were over a dozen translations of Beowulf that I set aside after the first twenty or thirty pages because they didn't speak to me. I settled on J. R. R. Tolkien's translation (silly me—I should have known better than to start with anyone else). Hearing Seamus Heaney read his translation reminded me that Beowulf is a poem—I've listened to Heaney's audio many times, not so much for the story but for the sound of the words. Watching Benjamin Bagby perform Beowulf in Old English while accompanying himself on the harp probably comes as close as possible to experiencing the story when it was told by traveling bards hundreds of years ago—I felt like young children might have, sitting with their families around the fire at night, catching only a word or two now and then, but understanding, through the bard's use of voice, expressions, and music, the gist of the story and its importance to my clan.

Three of the more tangential works I enjoyed were Beowulf for Cretins: A Love Story, by Ann McMan; Who's Afraid of Beowulf, by Tom Holt; and The Mere Wife, by Maria Dahvana Headley. I enjoyed The Mere Wife so much that, when I finished reading it in November, I searched for other work by the author.

And there it was: Beowulf: A New Translation, by Maria Dahvana Headley (her name bears repeating). Her version is lively, engaging, and more inclusive than others. Also, she pulls off a feat that amazes me: blending in words and phrases that might be heard on the streets of a big city today. The cover art is striking, too: I'm thinking about using the last handful of my fabric stash to make a wall hanging based on that design. I consider the book my gift from the universe for making it—almost—through this bugaboo of a year.

Kate Boyes’ debut novel, Trapped in the R.A.W., was released by Aqueduct Press in 2019. Kate is also the author of a biography of Paul McCartney, and her nature essays have been published in many anthologies, including two volumes of the American Nature Writing series. She lives on the Oregon coast and falls asleep every night to the sound of the surf.

No comments:

Post a Comment