Pleasures of Reading, Viewing, and Listening in 2020

by Lisa M. Bradley

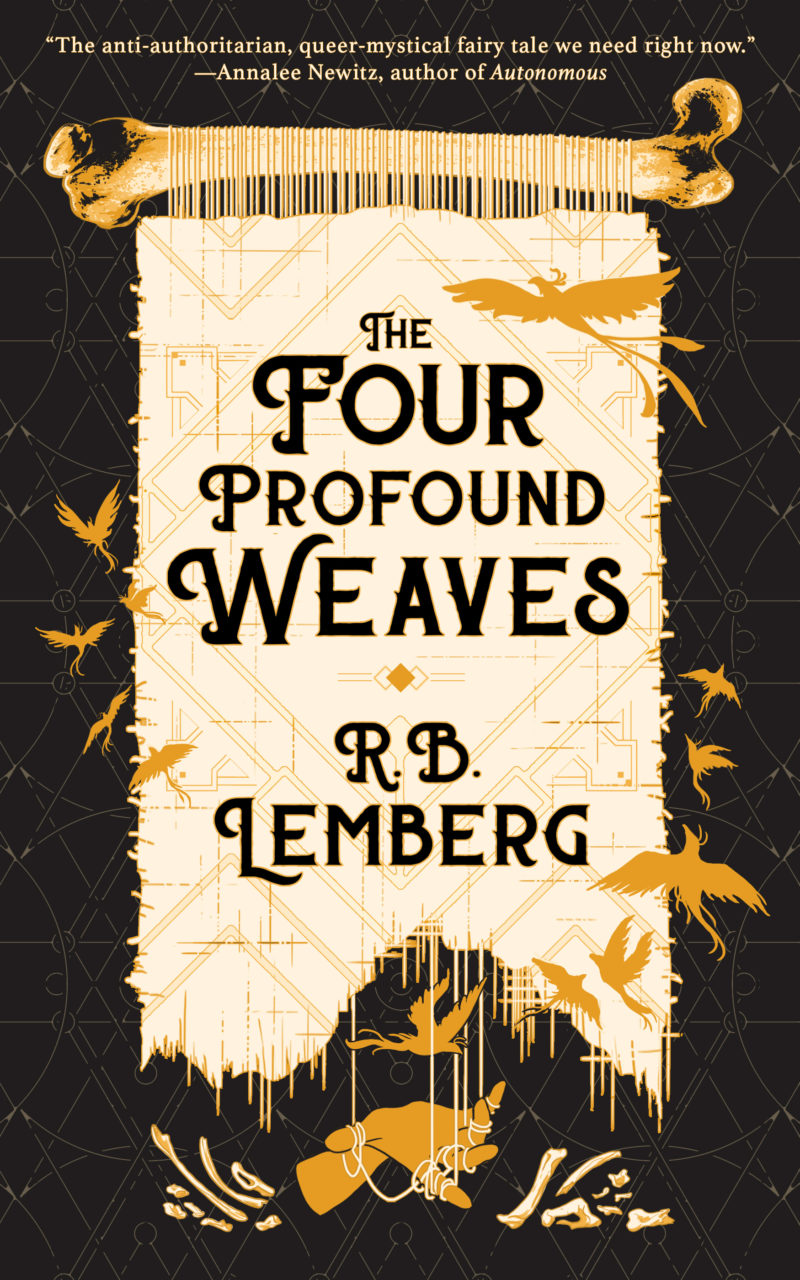

In December 2019, I read a galley version of R.B. Lemberg’s novella The Four Profound Weaves. I’ve read and admired R’s work for years, we’ve worked together, and by now I consider them part of my found family. So I knew their tale of trans elders on a desert quest—one to earn his new name; the other to learn the final weave of her craft—would be a good book. I didn’t realize it would be the most satisfying book I’d read in years. Nor could I have known that this book would brace me against the trashfire of a year that was fast approaching.

The Four Profound Weaves accepts that bad things, terrible things, happen and some of them cause irreparable harm. This acknowledgment, in itself, feels like solace, a kind of release. Nevertheless, the world keeps turning; change is inevitable; there must be light. R’s novella reminds us that even we flawed, hurting human beings can be agents of change. With love, commitment, and sacrifice, we can make things better. Sometimes, we win.

If ever we needed that message, it was in 2020.

By April, my family was in Covid-19 lockdown. The perverse vindication I’d felt at having my worst fears confirmed had quickly dissolved. Cabin fever hadn’t set in, but life felt like an endless doomscroll—until suddenly, it wasn’t. To quote Dave Grohl, frontman of the Foo Fighters, “thank god for the new Fiona Apple record!”

Fetch the Bolt Cutters dropped out of the blue, and it’s my favorite Apple album since Extraordinary Machine. Certainly the title song, with its lyrics “Fetch the bolt cutters, I’ve been in here too long,” rings with quarantine synchronicity, but it’s Apple’s magniloquent anger that always thrills me. Whether by breathily sweet soprano (“I would beg to disagree, but begging disagrees with me”), chest-deep bellowing (“Kick me under the table all you want, I won’t shut up”), or hissing snarl (“I resent you for presenting your life like a fucking propaganda brochure!”), Apple voices a righteous defiance, a rage even, that I usually leave on the page.

The flipside of that anger is a deep, indelible yearning for connection with other women. In one song, Apple empathizes, intimately, with her abusive ex’s new girlfriend. Another song was written in response to the allegations of sexual assault against Brett Kavanaugh, who was nevertheless sworn in as a Supreme Court Justice.

For the aptly titled “Ladies,” she intones, “Ladies, ladies, ladies, ladies…” before telling her ex’s new girlfriend she’s welcome to anything Apple may have left behind in his apartment, especially that dress in the closet:

“…don’t get rid of it, you’d look good in it

I didn’t fit in it, it was never mine

It belonged to the ex wife of another ex of mine

She left it behind, with a note…

She was very kind.”

To Apple, the men are interchangeable; it’s the women who matter. The best example, in song and real life, is “Shameika,” Apple’s song about being able to endure childhood bullying because Shameika, a self-assured schoolmate, “said I had potential.” Both girls left the school soon after, but each remained in contact with a favorite teacher, whom Apple describes as “Indiana Jones as a woman.” When Fetch went big, that teacher put the women in touch with one another, letting Shameika know how powerful her words had been and sparking their musical collaboration.

With the school year shortened by quarantine, I felt the need to supplement my teen’s formal learning, so I gave him a list of literary “classics” we could read and discuss together. When I pulled those books off my shelf, however, I discovered the classics I’d been saving for years were falling apart. Once I’d restocked, my kid chose to read Edgar Allan Poe, but I ended up rereading Animal Farm and 1984 by George Orwell, too. They seemed kinda relevant, y’know?

I’d forgotten that Rage Against the Machine’s “Testify” lyrics—“Those who control the present (now) control the past. Those who control the past (now) control the future.”—are a Party slogan in 1984. So I’m glad I reread both books, but as in high school, I think Animal Farm is the better of the two. It says everything 1984 does in far fewer pages, eliding the torture scenes and “universal” themes of sexual/romantic love. The fable form also permits sly word play and grim humor, making the bitter pill of this hard year a little easier to swallow.

Parceled out in carefully structured tweets, often including three or four images—usually an animal photo, a fashion or food image, and a landscape—Anne Louise Avery’s serialized tales of Old Fox, Wolf, Pine Marten, Ermine, Mouse, and other critters gave me life in 2020.

In a year when the news cycle just would not stop, Avery’s stories made time stand still. When my world felt brutal, relentless, hopeless, and lonely, a tweet from Avery (@annelouiseavery) offered instant comfort: In Old Fox’s world, friends tend to their sick, support each other’s dreams, nourish and shelter one another. If that world were pure escapism, it would be enough.

Sometimes, however, the struggles of our world seep into Fox’s. The critters’ heartache can be as sharp and profound as our own, as when Ermine scolds herself for ever imagining she could be a writer or when Wolf learns the death toll of “the Great Sickness” that is sweeping his world: “He wrote the number carefully in his diary & thought of each soul, earthy & loved as roses, high & holy as falcons, fire stars raken into the breath of night.” But Avery never abandons us to despair. Like R.B. Lemberg, Avery has the ability to touch our deepest bruises ever so lightly, acknowledge the ache, and begin the healing.

I tried to conjure a pithy label for Michael Jay McClure’s Twitter thread, but bless him, he gave us a hashtag. For 31 days leading up to Election Day, McClure (@mjmimages), an art historian and co-host of Bad Quarto podcast, posted pictures of stunning gowns (or equivalents) that Vice President Harris might wear to the Inauguration Ball. (Note, this was not the usual reduction of a woman politician to her fashion choices. McClure worked for and contributed financially to Harris’s campaign.) This was a whimsical approach to get-out-the-vote that encouraged us to imagine a brighter future.

Now, I don’t fashion. Like, at all. I use my poet’s license to avoid ironing clothes or brushing my hair. Still, I couldn’t wait to see McClure’s choice each day. The dresses were amazing, sometimes astounding; the pantsuits were devastating; the colors out of space; the shoes drool inducing. In addition to being visually stunned and strangely aroused, I learned so much—even from the comments section! For instance, I didn’t know that a stylist can specialize in dresses, but leave shoes and accessories to someone else (although, in retrospect, it seems obvious). I never thought about how heavy a swagged velvet dress could be or that it needed structural engineering so it wouldn’t sag or tear itself apart. And I was always astonished at what colors and combinations different people found attractive.

For a few minutes every day, I allowed myself to dream of seeing the first woman, first African American, and first Asian American Vice President dressed to the nines at a glamorous celebration. I let myself hope that in 2021, we’d have reasons to celebrate.

Turns out, hope is a muscle. The more you use it, the stronger it gets.

A queer Latina and devout murderino, Lisa M. Bradley writes about legacy, liminal people and places, and a truckload of taboos. Her collection of short stories and poetry is The Haunted Girl (Aqueduct); her debut novel is Exile (Rosarium Publishing). She served as Poetry Editor for Uncanny Magazine’s special issue, “Disabled People Destroy Fantasy,” and co-edited, with R.B. Lemberg, the Ursula Le Guin tribute poetry anthology, Climbing Lightly Through Forests (Aqueduct). Find her on Twitter (@cafenowhere) or visit her sometimes updated website: www.lisambradley.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment