by Mark Rich

I remember nodding over Samuel Butler's Erewhon nightly during the summer, often re-reading pages because the sleepy mind one night little recalled the words over which eyes had shut, the night before. Giving Erewhon a first reading took me months. Yet at times I wondered about it being a first. Later in the fall when I began The Way of All Flesh I found notes I made a few years before, taken from pages late in that book. Obviously I had read the novel — maybe as a remedy for wakefulness. My drawing such a blank about it, though, called for a re-reading ... later. The first few pages, at that point, were proving too powerfully remedial.

Later yet, when I was finding that Dickens's David Copperfield was woefully exacerbating my bedtime wakefulness, I encountered passages that instantly provoked a thought that had occurred to me before, at that very spot in the novel. So it seemed at the moment, anyway. Had I read it before? How can I say? Some books disappear from mind, the latter deeming the former forgettable — maybe having found itself insufficient to the task involved in understanding the experience. I suspect that life's requirements also have something to do with it — such as the ones that kept me overly busy and sometimes exhausted through this summer and early fall.

I undertake some books knowing that I will not retain them and that I must keep them at hand, for later reacquaintance and eventual, to-be-hoped-for friendship — as I do with poetry. "That which we had we still possess ... That which is lost we did not own." Thus Ella Wheeler Wilcox states the situation, with regards to the way of all books. Her Maureen and Other Poems I was reading when putting 2014 to bed. I have revisited it this year, and will open it again, with fondness and curiosity. The next poetry collection I read, sent to me out of sheer thoughtfulness by Alistair Rennie from Scotland: The Poems of Leopardi, translated by Geoffrey L. Bickersteth. I read the poems over days or weeks, then returned to Bickeresteth's lengthy opening comments, which made me hungry then to re-approach the poems, although that I postponed.

Leopardi, along with the poet named Vanolis, influenced Scottish poet James Thomson, "B.V.," whom I admire. In Leopardi's poems — as in the line, "above our cradle and our grave sits nothingness" — a personal desolation emerges that could be said to go missing in Thomson's works by no one who has read them. Fidelity to art links the two, as well, even if I suspect Leopardi's approach took a more austere turn than did Thomson's; yet I can see Thomson embracing the Italian's statement that the poet must achieve two aims in the art: clarity and simplicity. I also suspect that Leopardi's objections to the Romantics on grounds related to these two aims had its equivalent in Thomson's accepting Poe's rationalism over earlier transcendental aspirations. (Fortuitously, I found at a thrift store Penelope Fitzgerald's The Blue Flower, and was reading it around the time I was reading Leopardi. Fitzgerald's novel, based on the life of Georg von Hardenberg, moves along with alacrity to its end, which, oddly, falls before von Hardenberg adopts the name Vanolis and becomes known as a poet.)

That adjective "transcendental" brings to mind an image from Van Wyck Brooks's Helen Keller, Sketch for a Portrait. Helen's companion Polly takes Brooks unannounced to the study where Helen is reading. When Polly opens the door and turns on the light, Brooks sees Helen's face transfixed with joy. Only gradually, in separating herself from her reading, does she, to use the common phrase, come down to earth to the degree that she could interact with her visitors. If Keller encountered Leopardi's works she might have loved him as she did Plato. At least she would have appreciated his describing the creative process in terms of the mind taking in reality sympathetically. Bickersteth wrote, "the 'wreckage' of the real in the ideal is accompanied by, or results in, a feeling of intense pleasure, the only positive pleasure Leopardi recognized as possible in this life." When I re-encountered it the other day, this passage also recalled the scene above, with Helen Keller at work in her dark study, quietly ecstatic.

While I greatly admire Brooks's writings, this book takes a special place among them. In reading about Helen's global travels and her many hospital visits after World War II, it occurred to me that the single greatest witness to Modernity's final throes may have been deaf and blind.

In recent years I have read through old poetry books for children. This last winter I read, instead, Andrew Lang's The Blue Fairy Book and The Arthur Rackham Fairy Book; and, in the same vein, Collodi's Pinocchio and Louisa May Alcott's Flower Fables. I know with certainty that I never read the last, before. Collodi's tale I doubt I had read in its full form. What a naughty boy, that marionette! Had I known his story better as a child, I might have boosted my naughtiness beyond the mere mediocrity that I achieved.

Pinocchio falls, a bit roughly, into the Gothic wonder-tale tradition. I indulged in a small Gothic wonder-tale fest in February, reading Vathek, The Castle of Otranto, and the 1818 edition of Frankenstein. In the following two months, I indulged in a 1910s and '20s Harold Garis fest (Tom Swift and His Airship, Don Sturdy in the Land of Volcanoes, etc.) while also taking in, and truly enjoying, William Dean Howells's A Traveler from Altruria and Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Although Dickens felt most fondness for Copperfield, and although so far I am agreeing with Chesterton that his greatest novel may be Bleak House, Two Cities has such beauties in its writing and design that I doubt I will wait long before revisiting it.

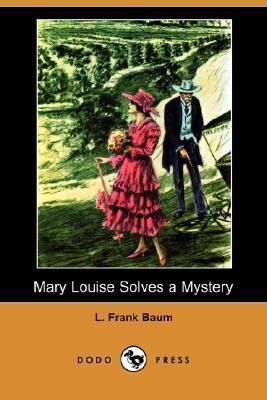

Over the summer and early fall I succumbed to pecuniary considerations and worked such hours at being antiquer, scrounger, and flea, that in reading terms I went nowhere, or Erewhon, as I noted at the start. The constant scampering had its rewards, as when an auction yielded some rare Baum titles. A book dealer at this outdoors event had no clue why I bought what I did, since Baum wrote these pseudonymously. Earlier, in May, I had read his Mary Louise Solves a Mystery, and found in it an element not unusual in his stories: a young-women's cooperative effort, set in contrast to the society of bankers and businessmen. The latter sorts often appeared in various shades of villainy in the Modern wonder-tale tradition, from Verne to Garis.

It may have been fitting that I should be falling asleep over Butler while antiquing, insofar as Martha and I were gathering to us property while at night I could be re-reading the words, "We are all robbers or would-be robbers together," in Erewhon. "Property is robbery." And afterwards in deciding against The Way of All Flesh I settled upon and delighted in two books, the second being Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, in which someone's thoughts, maybe Mrs. Dalloway's, turn upon the notion that an "unseen part" of us may attach to places or objects: so that in attending auctions and buying antiques we could see ourselves as investing in ghosts with which to fill our already haunted house to bursting. In Dalloway, this passage amused me: "Why could he see through bodies, see into the future, when dogs will become men?" For the prior book I settled upon and delighted in was by Clifford Simak. In the 1990s at some point I undertook to read all the Simak I could find, which amounted to a nice book-stack. Ring Around the Sun had evaded me, though. I found it strong with the Simakian dream-vision that makes for such pleasant reading.

It may have been fitting that I should be falling asleep over Butler while antiquing, insofar as Martha and I were gathering to us property while at night I could be re-reading the words, "We are all robbers or would-be robbers together," in Erewhon. "Property is robbery." And afterwards in deciding against The Way of All Flesh I settled upon and delighted in two books, the second being Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, in which someone's thoughts, maybe Mrs. Dalloway's, turn upon the notion that an "unseen part" of us may attach to places or objects: so that in attending auctions and buying antiques we could see ourselves as investing in ghosts with which to fill our already haunted house to bursting. In Dalloway, this passage amused me: "Why could he see through bodies, see into the future, when dogs will become men?" For the prior book I settled upon and delighted in was by Clifford Simak. In the 1990s at some point I undertook to read all the Simak I could find, which amounted to a nice book-stack. Ring Around the Sun had evaded me, though. I found it strong with the Simakian dream-vision that makes for such pleasant reading.

I had read a few other science fiction novels during the year, more or less on whims, and recently engaged in my tradition of the past few autumns, finding my way to a city magazine rack and buying a future-fantasy magazine or two — to see if anything might leap out and drag me up from antiques burial. This year I found two magazines, and have read one, the December Asimov's. While I found artificiality dominating, I liked some pieces well enough, and think it worth mentioning one story as having promise: Amanda Forrest's "Of Apricots and Dying," which features a setting not much removed from ours, in technologic terms, and which centers around a family whose dynamics provide the interest. As a tale full of deceit, among family members and between author and reader, it naturally has its artificial elements and manipulations. Yet it reaches without overreaching, and uses a style solid enough that I shook my head sadly, as opposed to rolled my eyes, at the adjective in "gifted jewelry." (With this paragraph I can face any who accuse me of being completely out of touch, and reply that they are only ninety-nine percent correct.)

Lately I have re-read Kathryn Rantala's The Finnish Orchestra, which I first read last December. These poems center on ancestors, landscape, and the old photographs that link the two and that appear alongside her words; and these words have the delicacy of cellophane gingerly peeled off old tea boxes — if that makes sense to anyone. I cannot make Rantala's poems my own, in the Wheeler Wilcox sense, yet emerge from them still interested and somehow satisfied.

At present, having unearthed the book from its summer-fall antiques entombment, I have started over again The Education of Henry Adams, in which I have just encountered the words, "The world never loved perfect poise. What the world does love is commonly absence of poise, for it has to be amused." (Perhaps Adams never met Mr. Turveydrop. Helen Keller, on the other hand, met "a quiet apologetic man who had a fist of iron" — so apparently met Uriah Heep.) Early in the year I read (for the first time that I recall! — although I believe I possessed the Whitman edition as a child) The Swiss Family Robinson in what seems a responsible translation — not a skimpy abridgment, in other words. In it I found the line, "I held the flamingo under my left arm, and my gun in my right hand." What perfect poise! — of a sort I aspire to, myself, so long as the flamingo is plastic and the gun, a ray-gun.

Mark Rich is the author of a major biographical and critical study, C.M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary, published by McFarland. He has had two collections of short fiction published — Edge of Our Lives (RedJack) and Across the Sky (Fairwood) — as well as chapbooks from presses including Gothic and Small Beer. With partner-in-life Martha and Scottie-in-life Sam, he lives in the Coulee region of Wisconsin where an early-1900s house, a collection of dilapidated antique furniture, and a large garden preoccupy him with their needs. He frequently contributes essays to The New York Review of Science Fiction and The Cascadia Subduction Zone.

No comments:

Post a Comment